West Chester University

Digital Commons @ West Chester University

Anthropology & Sociology College of Arts & Sciences

1-1999

West Chester University of Pennsylvania, mbecker@wcupa.edu

Follow this and additional works at: h>p://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/anthrosoc_facpub

Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons

=is Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Anthropology & Sociology by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more

information, please contact wcressler@wcupa.edu.

Recommended Citation

Becker, M. J. (1999). Etruscan Gold Dental Appliances: =ree Newly "Discovered" Examples. American Journal of Archaeology, 103(1),

103-111. h>p://dx.doi.org/10.2307/506579

Etruscan

Gold

Dental

Appliances:

Three

Newly

"Discovered"

Examples

MARSHALL

JOSEPH

BECKER

Abstract

Dental

appliances

fashioned from flat

gold

bands

are

known from

references

in

ancient Roman literature and

have been recovered from

archaeological

contexts since

the late

18th

century.

Wire

appliances

of

gold

and

silver

are known from the eastern Mediterranean

and have

completely

different

origins

and functions. Recent re-

search on

the

known

corpus

of these ancient

appli-

ances,

many

of which have been

lost,

provides

consider-

able

insight

into their cultural uses as well as their

place

in

dental

history.

Of

considerable interest are three Etrus-

can

examples,

now

lost,

that were

brought

to the United

States

in

the

19th

century.

The

origins

and

configura-

tions of these three

appliances

are discussed here

to

augment

what

is known

about other Etruscan

examples,

of

which

only

20

can be documented and nine survive.

All

appear

to have been used as decorative bands

or

to

support replacements

to one or both

upper

central inci-

sors of women from

whom

healthy

teeth had been re-

moved

deliberately.*

The Etruscan

origins

of

gold

dental

appliances,

around the

middle

of the seventh

century

B.C.,

have

long

been

recognized.1

These

appliances

are all fash-

ioned from flat

gold

bands,

and used to

hold

a

false

tooth

or

teeth

in

place

or to stabilize teeth loosened

by

periodontal

disease. Several lists of these

appli-

ances have been

presented

over the

past century,

but

attempts

to

generate

a

complete catalogue

have

long

been thwarted

by

the

presence

of numerous modern

copies,

poor descriptions

in

the

literature,

and

by

er-

roneous

identifications

of

various other

objects

as

examples

of ancient dental

work.

Many

false

examples

of ancient dental

appli-

ances have been

created

by

publishing photographs

of

them

upside

down,

or

by reversing

the

negative

in

making

a

print.

Thus a

single object

can

be

turned into four

examples

through

errors in

the

making

or use of

a

single

photograph.

The

negative

of

an

appliance

believed

to be fitted

to the

upper

rightjaw,

when

printed

backward,

appears

to

repre-

sent

an

appliance

from

an

upper

left

jaw.

When

in-

verted these two

prints

become four

examples,

but

all

may

derive from a

single negative.

While

this

might

seem a

simple

problem

to

correct,

only

an

important

recent

study by

L.

Bliquez

has

resolved

many

of

these

issues.2

The

following

observations

derive

from a

project

to

identify

and

describe

in

detail all the

known ex-

amples

of Etruscan

gold

dental

appliances

and

other

ancient dental

prostheses.

During

an

exhaustive

search

of

the literature three Etruscan

examples

were

identified as

having

been

brought

to the United

States,

but

were lost about

100

years ago.

ANCIENT DENTAL

APPLIANCES

An effort

to reconcile the

very

limited

archaeolog-

ical evidence with

direct information from

the

study

of Etruscan dental

appliances

and the teeth

associ-

ated

with

them has further

expanded

understanding

of this

subject.

Two sources of

information ne-

glected by previous

studies

have

significantly

ad-

vanced our

understanding.

First,

the direct

evidence

*

This

project

was

conducted while

I

was

a

Consulting

Scholar

to the

Mediterranean

Section of the

University

of

Pennsylvania

Museum of

Archaeology

and

Anthropology.

I

would like

to thank Donald

White,

Curator of

Mediterra-

nean

Archaeology,

for

his

encouragement

and

support

of

this

research.

My

sincere thanks

are also

due

John

Bennet

and

an

extremely

careful

anonymous

AJA

reviewer for

their

contributions to

the

completion

of

this

manuscript,

and

to the

many

other

people

who

helped

in

so

many

dif-

ferent

aspects

of this

research.

Special

thanks

are due

Larissa

Bonfante and

Ingrid

Edlund

for their

help

in

guid-

ing

this

project

in

its

earliest

phases

and

to

Lawrence

Bliquez

and

John

Robb

for their

generous

sharing

of im-

portant

data

relating

to

my general

study

of

ancient dental

appliances.

A

portion

of

the

information

concerning

Wil-

liam

Barrett was

originally gathered

in

1991 at

the

request

of

William

Feagans,

Dean of

the

Dental

School at

the State

University

of New

York

at

Buffalo.

Those

data were

incor-

porated

in

the museum

display

then

being organized

for

the 100th

anniversary

of the

Dental

School. The aid

of

Dean

Feagans

in

my

search for

these

appliances

in

Buffalo

is most

gratefully

acknowledged.

I

E.

Gaibrici,

"Necropoli

di

eta

ellenistica

a

Teano

dei

Sidicini,"

MonAnt

20

(1910)

cols.

44-45;

L.

Bonfante,

"Daily

Life and

Afterlife,"

in

L.

Bonfante

ed.,

Etruscan

Life

and

Afterlife

(Detroit

1986)

250.

2

L.

Bliquez,

"Prosthetics in

Classical

Antiquity:

Greek,

Etruscan,

and

Roman

Prosthetics,"

ANRW 37:3

(1996)

2640-76. See also

M.J.

Becker,

"Spurious

'Examples'

of

Ancient

Dental

Implants

or

Appliances,"

Dental

Anthropol-

ogy

Newsletter

9:1

(1994)

5-10;

Becker,

"A Roman

'Implant'

Reconsidered,"

Nature

394

(1998)

534;

and

Becker,

"An-

cient

'Dental

Implants':

A

Recently

Proposed

Example

from

France

Evaluated with

Other

Claims,"

International

Journal of

Oral and

Maxillofacial Implants

14

(in

press).

103

American

Journal

of

Archaeology 103

(1999)

103-111

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

104 MARSHALL

JOSEPH

BECKER

[AJA

103

from

odontometrics-the measurements of the

ele-

ments that make

up

these

appliances

and/or

any

teeth that have

survived-suggest

that

only

Etruscan

women wore

them.3

Second,

detailed

examination

of

the extant

examples

has

yielded precise

informa-

tion

regarding

their

construction.4

When

combined

with the extensive

archaeological

data,

this new

evi-

dence seems to confirm that

gold

dental

appliances

were worn

only by

Etruscan

women,

suggesting

that

cosmetic concerns were

paramount

in

their

cre-

ation. This accords

well with what

is

known

about

Etruscan women and their

public presentation.

The

decline

of Etruscan culture

in

the face of

growing

Roman

dominance also

may

explain why

these

appli-

ances

appear

to have faded from

view,

probably

in

a

pattern parallel

to the

decline

in

the use of

the

Etrus-

can

language.5

The

literary

evidence for Roman

use

of dental

prostheses

remains

unsupported by

ar-

chaeological

evidence.

Different

mortuary

customs

among

the

Romans

may

have resulted in

the

re-

moval

of

gold

appliances

before

interment,

or the

use of

these decorative

items

may

have been

re-

stricted to

Etruscans

living among

the

Romans.

Direct and

detailed

study

of the nine

surviving

Etruscan

appliances

and,

whenever

possible,

the

few

teeth that

survive has been

basic to the creation of

a

new

catalogue.

Also

included

in

this

new list are

the

six

known "Eastern"

wire dental

appliances

associ-

ated with the

later

Phoenician tradition.

These

are

fashioned from

gold

or

silver

wire,

but

appear

to

have

served

purposes

distinct from those of

the Etrus-

can form.

The Eastern

appliances,

however,

were

only

worn

by

men.6 A

catalogue

incorporating

all

of

the

known

appliances

as well as

some

suspected

ex-

amples

also

enables us

to

identify

copies,

of

which

many

exist,

as well

as

specious

examples

of

appli-

ances

and

objects

that

have been considered

to

be

dental

implants.7

Intensive

searching

of the

archaeological,

dental,

and technical

literature

has revealed

two

examples

that

had

come to

the United

States

and were

not

noted

in

previous

catalogues.

A third

and

nearly

un-

known

example

was also

brought

to

America

about

the same

time.

All three

of these

specimens,

now

lost,

were

originally

published

in

obscure

journals.

In this article

I

collate

the evidence

on these

pieces

and assess

their

contribution

to our

understanding

of this

important

aspect

of Etruscan

technology

and culture.

THE

BARRETT

APPLIANCES

William

C.

Barrett,

first Dean

of the Dental

School

at the

State

University

of New York

at

Buffalo,

was

a

friend

and

colleague

of

James

Gilbert

Van

Marter

(1835

-

1901),

who

practiced

dentistry

in Rome

dur-

ing

the

1880s.

Barrett

held

his D.D.S.

from

the

Uni-

versity

of

Pennsylvania

(1881)

and

appears

to

have

known

Van Marter

from

his student

days.

Barrett's

interest

in

early dentistry

led

him to

ask Van

Marter

to

secure

examples

of Etruscan

gold bridgework.

Van

Marter,

who had

been

studying

the Etruscans

for

"several

years,"

notes

that

he had

been visited

in

Rome

by

the

lateJ.

Marion

Sims.8

The

date

of

Sims's

death,

ca.

1880,

may provide

a

clue

to the

length

of

Van Marter's

residence

in

Rome.

Wolfgang

Helbig,

an

important

figure

in Italian

archaeology,

intro-

duced

Van Marter

to

C.

Dasti,

who

was

an

archaeolo-

gist

and

mayor

of

the

village

of

Corneto

(now

re-

named

Tarquinia),

at

the center of

the

south

Etruscan

area

from which

these

ancient

dental

appliances

most

likely

originate.

Barrett

was

also the

editor of

the

Independent

Prac-

3

F.W.

R6sing,

G.

Paul,

and

S.

Schmitenhaus,

"Sexing

Skeletons

by

Tooth

Size,"

in

R.J.

Radlanski

and H.

Renz

eds.,

Proceedings of

the

10th

International

Symposium

on

Dental

Morphology

(Berlin

1995)

373-76;

also

M.J.

Becker,

"Re-

constructing

the Lives of

South

Etruscan

Women from

the

Archaeological,

Skeletal,

and

Literary

Evidence,"

in

A.E.

Rautman

ed.,

Interpreting

the

Body:

Insights from

Anthropologi-

cal and

Classical

Archaeology

(Philadelphia,

in

press).

4

M.J.

Becker,

"An

Etruscan

Gold

Dental

Appliance

in

the

Collections of

the

Danish

National

Museum,"

Tanlaege-

bladet

96:15

(1992)

695-700;

see

also

the

following by

Becker:

"Etruscan

Gold

Dental

Appliances:

Origins

and

Functions

as

Indicated

by

an

Example

from

Valsiarosa,

Italy,"

Journal

of

Paleopathology

6:2

(1994)

69-92;

"Etruscan

Gold

Dental

Appliances:

Origins

and

Functions as

Indi-

cated

by

an

Example

from

Orvieto,

Italy,

in

the

Danish

Na-

tional

Museum,"

Dental

Anthropology

Newsletter

8:3

(1994)

2-8;

"Female

Vanity

among

the

Etruscans,"

Actas

del

I

Con-

greso

Internacional

de

Estudios sobre

Momias,

1992

(Santa

Cruz

de Tenerife

1995)

651-58;

and

"An

Unusual

Etrus-

can

Gold Dental

Appliance

from

Poggio

Gaiella,

Italy,"

Dental

Anthropology

Newsletter

10:3

(1996)

1-6.

5

M.J.

Becker,

"Etruscan Gold

Dental

Appliances:

Evi-

dence

for

Cultural

Processes,"

in

A. Guerci

ed.,

Health

and

Diseases:

Historical

Routes

2

(Genoa

1998)

8-19.

6

M.J.

Becker,

"Early

Dental

Appliances

in

the

Eastern

Mediterranean,"

Berytus

42

(1995/1996)

71-102.

See

also

D.

Clawson,

"Phoenician

Dental

Art,"

Berytus

1

(1934)

23-31.

7

M.J.

Becker,

Journal

of

Paleopathology (supra

n.

4);

and

Becker,

"Ancient

Dental

Appliances"

(unpublished

manu-

script).

8J.G.

Van

Marter,

"Some

Evidences of

Prehistoric

Den-

tistry

in

Italy,"

Independent

Practitioner

6

(1885)

1-5;

see

also

Van

Marter's

brief

summary

of

this

article in

"Prehis-

toric

Dentistry,"

Archives

of

Dentistry

2

(1885)

87-89.

This

information

also

appeared

as Van

Marter,

"Dall'odontoja-

tria nei

tempi

antichi,"

Giornale

di

corrispondenza

per

dentisti

14

(1885)

227-31.

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1999]

ETRUSCAN GOLD

DENTAL

APPLIANCES

105

titioner

(which

subsequently

became

the

International

DentalJournal),

and

published

two of

Van

Marter's

communications.9

Barrett

acquired

the teeth

before

1886,

as

well

as all of the items then

thought

signifi-

cant from this

tomb.

Helbig

had dated

the

tombs

on

the basis of his evaluation of the other materials

found

together

with these

appliances.10

Edlund con-

firms

Helbig's

evaluation.11

Van

Marter's letters to

Barrett describe the excava-

tion of several rich

Etruscan tombs

in

the area of

an-

cient

Tarquinia,

from

which

gold

dental

prostheses

were

often recovered.

By

1886,

Barrett's

request

for

some

examples

for his

private

collection resulted

in

two

being

sent

to

Buffalo.

After

the

first

appliance

(fig.

1)

had

arrived,

Barrett

requested

another,

to-

gether

with the

archaeological

materials from

the

same tomb. The

second

example

that Van

Marter

purchased

(fig.

2)12

was described

as follows:

The most

recently

opened

and the oldest Etruscan

tomb

yet

discovered

in

Italy

was

lately

excavated at

Capadimonte

[sic],

near the Lake of

Bolsena.

The

entire contents

of

this

tomb,

including

three teeth

bound

together

with a band

of

pure gold,

gold

spiral

rings

for the side

hair,

silver

finger

ring,

necklace of

amber

and

glass,

arm

band, bronzes,

vases, etc.,

etc.,

I

take

pleasure

in

sending

you by

first

express.

The

part

of

the find of interest to our

profession

is the

three

teeth,

a

drawing

of

which

I

send

you

herewith.

This tomb

belongs

to the

VIth

Century

B.C.,

or

about one hundred

years prior

to

the

dates

of

the

oldest

partial

denture

which I sent

you

last

year.

Both of the

Barrett

gold appliances

were

simple

bands,

within which

only

some of the

original

teeth

may

have remained.

Waite

suggests

that he

borrowed

both

pieces

in

1885,

and

exhibited them before

two

New York dental

societies.13

As noted

below,

a third

example

appears

to

have been

added to

this

collec-

tion

during

the

years

after 1885.

By

the time of Bar-

rett's

death

in

1903,

however,

the

location of

the

three

appliances

was

unclear,

and their

present

loca-

tion

remains

unknown.

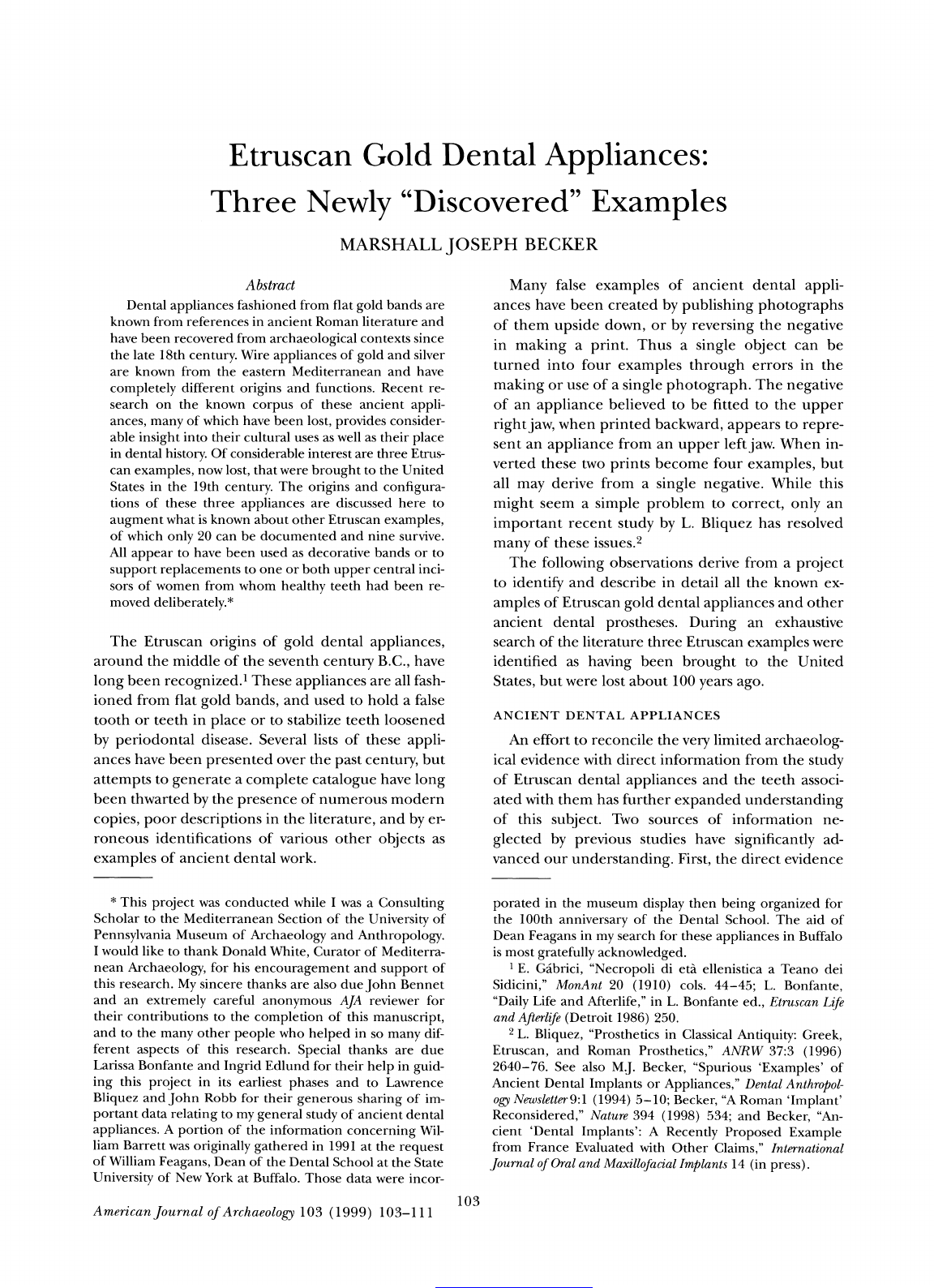

The Etruscan

gold

dental

appliance

that I

identify

as Barrett

I

(fig.

1)

had been

in Barrett's

collection

in

Buffalo,

New

York,

but its

present

location is

un-

known.

This

appliance,

from an unknown

source

in

Etruria,

is a

simple

band that

probably

had been

worn in the

upperjaw

of a

woman,

enclosing

at

least

three of

her

maxillary

incisors. The date

of this

pros-

thesis has

been

roughly

estimated to be

in

the sixth

century

B.C.

Only

one

obscure

publication,

by J.N.

Farrar

in

1888,

provides

us

with direct

information

concern-

ing

the

Barrett

gold

appliances.14

Two

years

prior

to

this

publication,

Van

Marter

made

a

reference

in

a

letter to an

example

that

now can

be

identified as

the

Barrett

I

appliance.15

In

that

letter Van

Marter

!

l

I

i

A

B

cccD

I

I

I

Fig.

1. The Barrett

I

appliance.

Dashed

lines

in A

indicate

theoretical

reconstructions;

the

dotted lines

in

B,

a

view

from

above,

mark the location

of the central

tooth

that

was

spanned

by

this

appliance;

and

C

represents

the

band

as it would

have been

seen from above.

(Views

A and

B

after

J.N.

Farrar,

Treatise

on the

Irregularities

of

the Teeth

and

Their Correction

I

[New

York

1888]

33,

figs.

6

and

8)

9

Van

Marter,

Independent

Practitioner

(supra

n.

8);

and

Van

Marter,

"Further

Evidences

of

Prehistoric

Dentistry,"

Independent

Practitioner

7

(1886)

57-61.

10

W.

Helbig,

"Scavi di

Capodimonte,"

RM 1

(1886)

25-26.

"11

I.E.M.

Edlund,

"A

Tomb

Group

from Bisenzio in

the

Barrett

Collection,

Buffalo,

NewYork,"

AJA

85

(1981)

81-83.

12

Van Marter

1886

(supra

n.

9)

59. A

pair

of

dental

ap-

pliances

brought

to

Hereford,

England

in

August

of

1885

appears

to

be the

Liverpool pair,

not

the

Barrett

pieces.

Spence

Bate,

of

the

Western

Branch

of

the British

Dental

Association,

suggested

using

funds at

hand

to

illustrate

these

pieces,

inasmuch as

the

Independent

Practitioner "did

not

circulate

largely

in

this

country."

This

would

appear

to

be

a

reference to Van

Marter's

article of

1886,

which

may

have been

known to

these

dentists

in

manuscript

form

prior

to

its

publication.

The

resulting

drawings, published

by

W.H.

Waite,

"Association

Intelligence,

Western

Coun-

ties'

Branch,"

Journal

of

the British

Dental

Association

[now

British

Dental

Journal]

6

(1885)

facing p.

512,

are of

the

pair

of

appliances

now

in

Liverpool.

Detailed

publication

of

the

Liverpool

appliances

is

forthcoming.

13Waite

(supra

n.

12)

316-17,

499-512.

See

also

Waite's item

under

"Pre-historic

Dentistry,

Specimens

Ex-

hibited,"

The

Dental

Record 5

(1885)

442-43.

14J.N.

Farrar,

Treatise on the

Irregularities

of

the

Teeth

and

Their

Correction I

(New

York

1888)

33,

figs.

6 and

8.

15

Van

Marter

1886

(supra

n.

9)

59.

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

106

MARSHALL

JOSEPH

BECKER

[AJA

103

I

I

B

?)Y

C

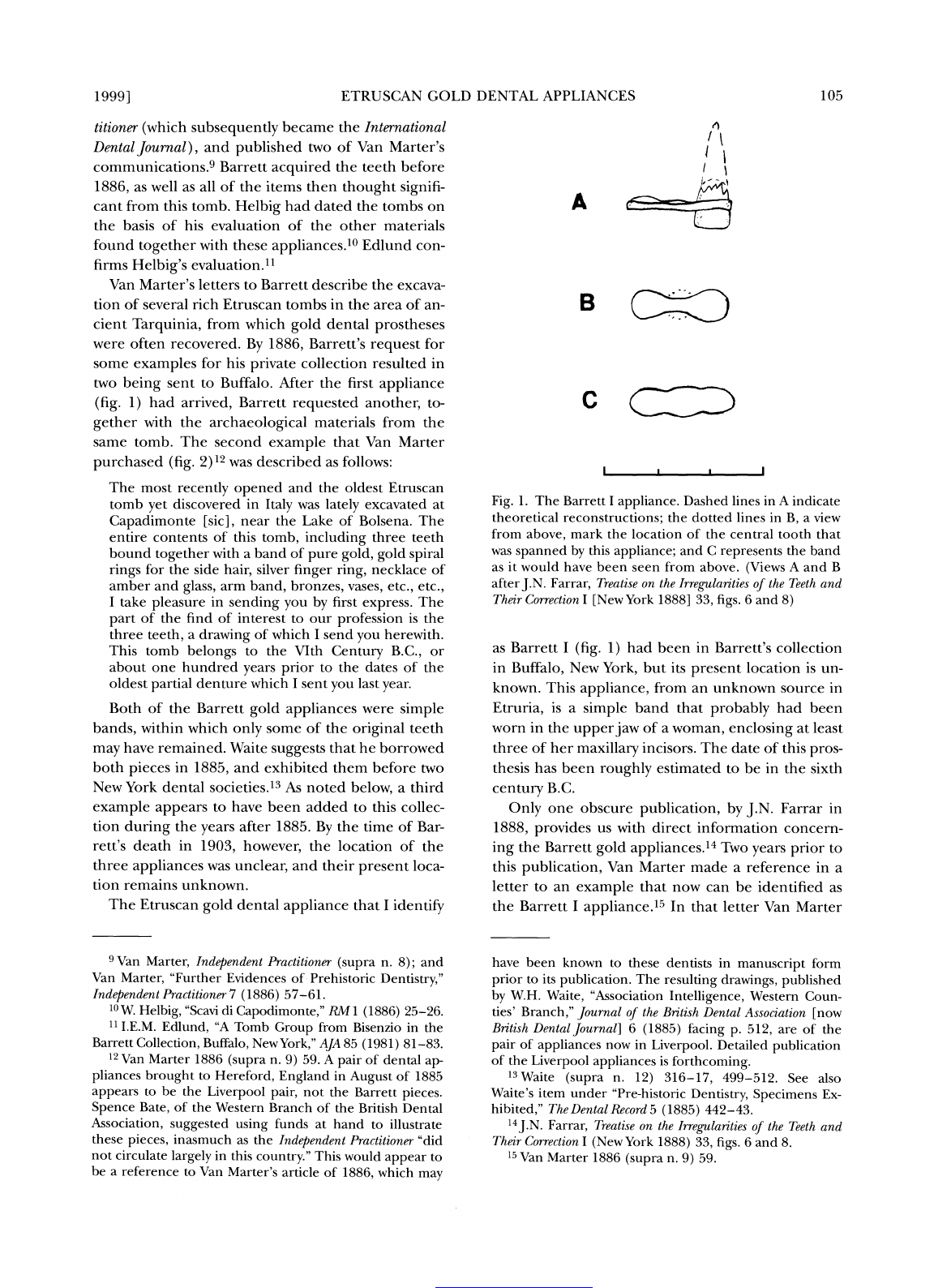

Fig.

2.

The

Barrett

II

appliance.

In

his

reconstruction,

Farrar had

inverted the

appliance,

which would

have been

worn

in

the maxilla.

Damage

to the teeth is

typical

of the

decay pattern

found in

examples

recovered from

Etruscan

chamber tombs.

(Views

A and

B

afterJ.N.

Farrar,

Treatise

on the

Irregularities

of

the Teeth

and

Their

Correction

I

[New

York

1888] 33,

figs.

5

and

7)

describes a tomb

belonging

to

the

sixth

century

B.C.,

"or

about one

hundred

years

prior

to the

dates

of the

oldest

partial

denture

which

I

sent

you

last

year"

[emphasis

mine].

This

suggests

that

around

1885,

the

year

before he

sent the "entire"

contents

of an

Etruscan tomb to

Barrett

(see

Barrett

II,

below),

Van

Marter had sent him

another

example

of

an Etrus-

can

gold

dental

appliance.

Van

Marter's

published

statement,

quoted

in

full

above,

can

be

understood

only by

reading

Farrar's

publication

relating

to the

first two

Etruscan

appliances

that

had been sent

to

Buffalo.

The

Barrett I

piece

clearly

was

excavated

prior

to

the

better-known

and

more

extensively

described

Barrett

II

example

(see

infra).

Farrar,

like

Barrett,

was born

and

raised

in

upstate

New York.

Farrar

must have

seen

the first two

pieces acquired

by

Bar-

rett while

he was

in

Buffalo,

or have

been

shown

both when

Barrett

was

touring

with these

appliances.

Lacking

data on

the

numerous

examples

then

known

in

Italy,

Farrar illustrated

his brief

text on

ancient

dental

goldworking

technology

with

the two

exam-

ples

that he had

near at hand.

This decision

is

quite

for-

tunate

for

us,

as

today

this

record

provides

the

only

il-

lustration

known

for the Barrett

I

appliance.

The second

simple

band

appliance,

identified

as

Barrett

II

(fig.

2),

was found

at Bisenzio

(Visentium)

at

Capodimonte

near Lake

Bolsena.

In

1886,

soon

after

its

discovery,

this

appliance

was

sent to

Barrett

in the United

States.

Along

with

the other

two

appli-

ances

owned

by

Barrett,

this

piece

disappeared

after

1903.

This

band also

had been

designed

to be

worn

in the

upper

jaw

of a

woman,

spanning

at least

four

and

possibly

five teeth.

A

date

of ca. 500-480

B.C.

has

recently

been

suggested

by

Edlund

for this

tomb

group, confirming

Helbig's

evaluation

in 1886

when

the tomb

was

excavated.

In

addition

to

Helbig's

and

Edlund's references

to the Barrett

II

appliance, eight

other

published

notes

make mention

of it.16 The

few

authors

who

attempted

to

describe

this

simple

appli-

ance,

without

having

it available

for

study,

have

done

little

more than confuse

their

readers.

Van Marter's

letter

of

1886,

quoted

above,

pro-

vides

a date for

this tomb

as well

as a

good drawing

of

the

appliance.

Helbig clearly

states

that all of

the

objects

in the tomb

containing

the Barrett

II

appli-

ance were

acquired

as a

group by

Van

Marter,

acting

as the

agent

for

Barrett.17

Van Marter

also notes

that

he

sent

this

piece

to

Barrett.

Farrar,

however,

offers

what

appears

to be

a different

account,

but

he

may

be

referring

to an

entirely

different

prosthesis.18

Far-

rar

says

that

the

excavation

took

place

in

1886

and

that the entire

contents

of the tomb

were

bought by

the

American

dentist William

Carr

and

presented

to

"W.C.

Barrett,

and

now

constitute a

portion

of his

private

museum. The

specimens

in

this

collection

are

especially

interesting

to

the

dentist

[including

carious

molars]."

The

possibility

that

this

is

the third

dental

appliance

that came

to

the

United

States,

as

discussed

below,

cannot be

ruled

out.

Alternatively,

Farrar

may

simply

have

confused

the

names

of the

16

These

publications,

in

order

of

their

appearance,

are

Van

Marter

1886

(supra

n.

9)

59-60,

fig.

3;

Helbig (supra

n.

10);

Farrar

(supra

n.

14)

33,

figs.

5

and

7;

C.R.E.

Koch

ed.,

History

of

Dental

Surgery

I

(Fort

Wayne

1909)

fig.

5;

F.

Weege,

"Das

Museum

der

Villa

Papa

Giulio,"

in

W.

Helbig,

Fiihrer

durch

die

offentlichen

Sammlungen

klassischer

Altertiimer

in

Rom3

II

(Leipzig

1913)

312-81;

K.

Sudhoff,

Geschichte

der

Zahnheilkunde2

(Leipzig

1926)

fig.

52

(and

the

later edi-

tions);

B.W.

Weinberger,

An

Introduction to the

History

of

Dentistry

1

(St.

Louis

1948)

125,

fig.

41.4;

Edlund

(supra

n.

11);

D.J.

Waarsenburg,

"Auro

dentes

iuncti: An

Inquiry

into

the

Study

of

the

Etruscan

Dental

Prosthesis,"

in

M.

Gnade

ed.,

Stips

votiva:

Papers

Presented

to

C.M.

Stibbe

(Amsterdam

1991)

n.

5:

no.

14;

and

Bliquez

(supra

n.

2)

"R,"

fig.

28.

17

Helbig

(supra

n.

10)

26,

n.

1.

18

Farrar

(supra

n.

14)

33.

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1999]

ETRUSCAN GOLD DENTAL APPLIANCES

107

principals

involved

in these

dealings.

In his

trea-

tise,19

he

provides

the

following

information:

Besides

these

teeth,

there were three that were

bound

together

with

a

gold

band;

also the crown

of

another

(central),

bound with a similar

devise.

Figs.

5 and 6 illustrate the

two

specimens,

and show

the

relation of the bands to the

teeth

in side view. In

Figs.

7 and 8 the

plain

lines show

the

top

view

of the

bands

detatched

[sic]

from the teeth as

they ap-

peared

when

I

saw them.

When

in

use, however,

these bands were

undoubtedly

bent

as shown

by

the

dotted lines. These bands were

probably

bound to

the teeth

with

gold

wire

as

shown

in

Fig.

9

[the

Gail-

lardot

gold

wire

appliance

now

in

the

Louvre;

fig.

3

here].

The tomb contained other

antiquities,

a list of

which

is

given

below,

as evidences of the

high

rank

held

by

the

occupants

of the

tomb,

and to show

that

consequently

these

specimens

of

denture were

prob-

ably

of

the

best

that the

period

afforded.

Farrar's

list of

artifacts

is as follows:

"two

spiral gold

rings,

incised hair

ornaments,

one

silver

finger

ring,

necklace

of

lapis

lazuli and

pure

amber,

bronze

placque

[sic]

nearly

2

feet

in

diameter

(with

lions'

feet

and sea

horses

in

full

relief),

one

large

bronze

vase with ear

pieces representing

the Taurian

Jove,

bronze

ornament,

evidentally

an

armour-piece

for

the

head,

bronze

wine-strainer,

silver

'fibrilla,'

two

bronze

cups,

four

earthen

jugs

(two

finely

molded),

two vase handles with carved head and

tail

pieces."

From Farrar's comments one cannot tell

if

the

two

appliances

came

from

this

tomb or

from two

sepa-

rate tombs.

Farrar

illustrates this

appliance

as

if it

were a mandibular

prosthesis,

an

extremely unlikely

possibility.

His

identification of this

appliance

as

mandibular, however,

may

reflect the

"position"

in

which

it

was

observed

during

the

excavation of

the

tomb.

A

second

premolar,

canine,

and central inci-

sor

appear

to be

present,

with one

space

between

each. Most

likely

this was a

maxillary prosthesis.

Weege's

list

of

dental

appliances

includes one

said

to come from

Capodimonte.

The

description

is

too

vague

to

identify

it

as

the Barrett

II

piece

or

yet

an-

other

dental

appliance,

and it

could even refer to

an

appliance

reportedly

from

Bracciano

that has

very

recently

come to

light

in

Austria.20

Also

of

impor-

tance

in

Weege's

text is the

reference

to

an

example

that

Van Marter

says

had been

sent to

Barrett

during

the

previous

year,

about 1885

(Barrett

I,

see

above).

Van

Marter's

description

of

the

Barrett II

appli-

ance

is not

very

clear,

nor

does

his

illustration enable

us to

recognize

details.2'

Van Marter's

poor descrip-

tion is

repeated

by

Helbig,22

who

suggests

that this

prosthesis

was worn

by

a woman

or

a

"giovinetta."

The

three

teeth,

bound

with

a thin

gold

band,

are

said

to

be the

upper

left lateral

incisor,

canine,

and

premolar. Helbig clearly

indicated that the band

might

only

have served

to

hold a

naturally

loosened

canine

in

place,

rather

than

serving

to hold a

trans-

planted

tooth in

that

position.

The

canine,

however,

is less

likely

to

have been

loosened

by

a blow or

peri-

odontal

disease

than

either

of

the

adjacent

teeth.

Koch

provides

a

poor

sketch,

probably

derived

from

Van Marter's

figure,

that

incorrectly

illustrates this

piece

as

mandibular.23

Farrar's

illustrations

show

a

simple gold

band that

appears

to have

extended

around five teeth.

This

type

of

band can be

used to stabilize

loose

teeth,

or

may

have been

purely

decorative. The

lack of

details

regarding

the

context

in

which it

was

found

and

complete

absence

of

associated

skeletal

material

prevent

us from

making any

determination of func-

tion.

The

three teeth

shown

by

Farrar's

illustration

A

C

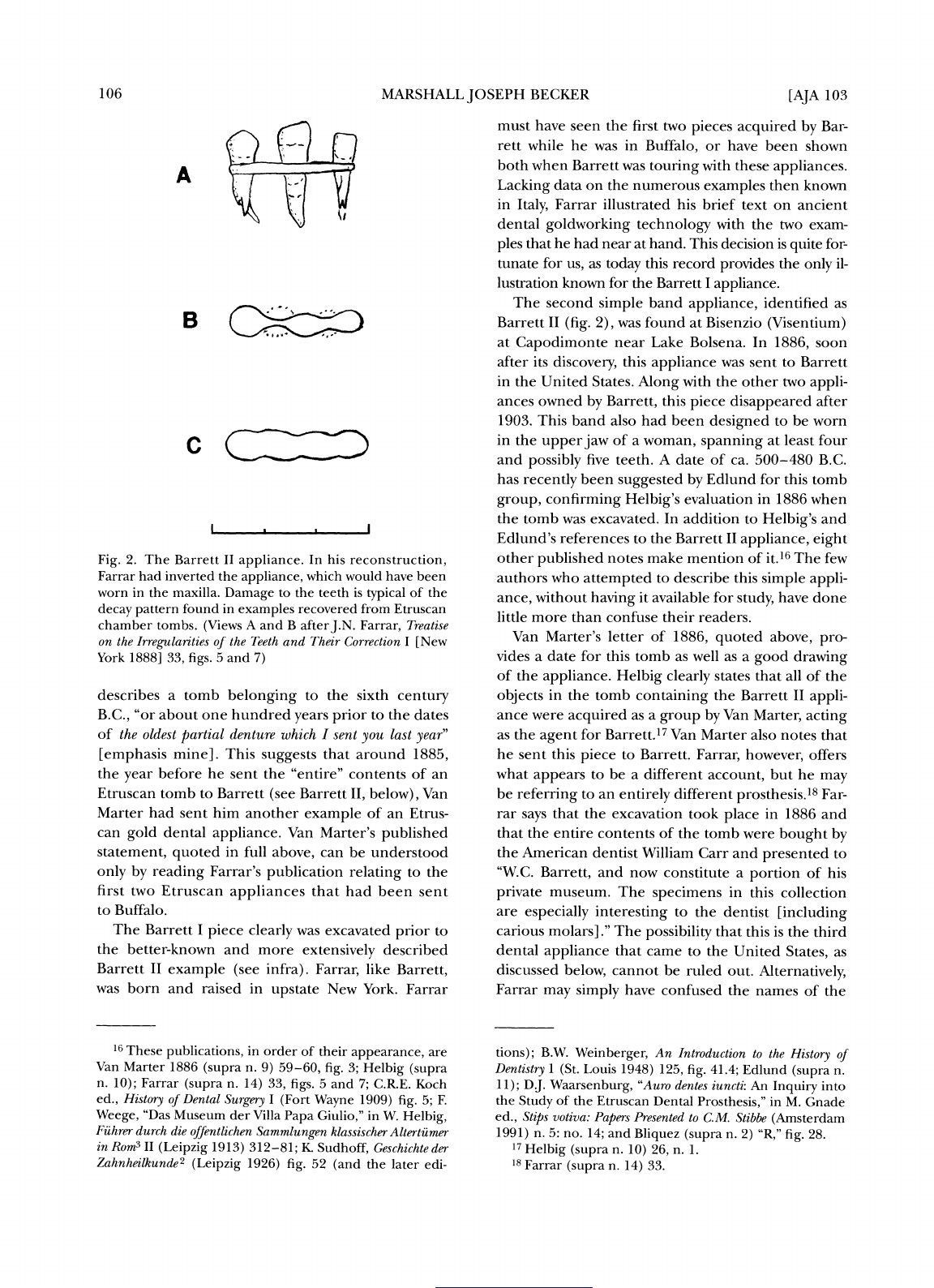

Fig.

3.

The

Gaillardot

appliance,

an

example

of

an east-

ern Mediterranean

gold

wire dental

prosthesis.

(From

M.J.

Becker,

Berytus

42

[1995/1996]

fig.

1)

19

Farrar

(supra

n.

14)

33.

20Weege

(supra

n.

16)

371.

A

possible

new

Etruscan

dental

appliance

said to

come from

Bracciano

recently

has

come to

light

in

Vienna;

see M.

Teschler-Nicola et

al.,

"Very

Early

Dental

Bridgework,"

Homo

45,

Suppl.

(1994)

132

(poster

abstract).

21

Van

Marter,

Independent

Practitioner

(supra

n.

8).

22Van

Marter

(supra

n.

8);

Helbig

(supra

n.

10)

25;

Koch

(supra

n.

16);

Bliquez

(supra

n.

2).

23

Koch

(supra

n.

16)

16,

fig.

5.

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

108

MARSHALL

JOSEPH

BECKER

[AJA

103

may

derive

from the

original

owner,

but

this is not

certain.

Possibly

two

of the five teeth held

within

this

appliance

were

lost

after

death,

and the

re-

maining

teeth

survived at

least

until

they

entered

Barrett's

collection.

Clearly

this

very

narrow

gold

band had

been

pinched together

in

the two

spaces

where teeth were

not

present

when

drawn

by

Farrar.

This

certainly

oc-

curred after

recovery

from

the

tomb,

as a

deliberate

effort

to retain the

surviving

three teeth within

the

band.

This

appliance

is

similar,

in this

respect,

to

an

example

from

Tarquinia

published

by Weinberger

in

which

the

thin band has

been

pinched together

in

the center where

it once embraced a

tooth.24

Weinberger

refers to the Barrett

II

appliance

in

his

text and

suggests

that

it

is

a mandibular

prosthe-

sis

enclosing

the

right

central and

lateral

incisors,

right

canine,

and

both

premolars,

with the teeth

il-

lustrated

representing

the central

incisor,

canine,

and second

premolar. Weinberger's

description

of

the

appliance

is

typical

of those derived

from

poor

photographs

by

individuals

who have

no

idea

how

these

appliances

were

made

or used.

Weinberger

states that this

appliance

is

a series

of

rings

con-

nected

by

spacing

bars

where the

first

premolar

and

second

incisor

are

missing.

Since most

of the

pub-

lished statements

on

this and almost

all of the other

known

appliances

include

descriptions

based

on

poor

illustrations and

vague speculations regarding

the actual

pieces,

we can

understand

why

so much

confusion

has entered

the literature.

The

Barrett

II

appliance

must have

been

recov-

ered about

1885,

and

Helbig provides

a

description

of

the

tomb

goods.25

He

suggests

that the

appliance

is from a "tombe a

fossa

che furono

scoperte

in

uno

strato

inferiore

a

quello

teste'

descritto,"

one

that

ap-

pears

to.be

early

fifth

century

B.C.

in

date.

Helbig

concludes

that the

earlier tomb with the

Barrett

II

appliance

dated

from

the sixth

century

B.C.,

and

that the

appliance

is thus

the

earliest

example

known.

Edlund

places

the

three

surviving

artifacts

that

were

recovered from

the tomb with

the

appli-

ance

in

the

fifth

century,

and a date of

500-480 B.C.

seems

reasonable.

Helbig's

evaluation of

the

date,

on

the basis of

Attic

vases

from

a tomb

at

Tarquinia,

did not

contradict his

statement

that at that time

this

was the

earliest known

example

of

a

gold

dental

ap-

pliance.

Only

in

1898 was

an earlier

example

discov-

ered

at

Satricum.

Helbig

also referred

to "Table

X,

8

and 9"

as

indicating

that

literary

sources offered

con-

firmation

of

the

antiquity

of these

appliances.26

Barrett died

in 1903. His estate

supposedly

was

di-

vided between

the

University

and

the Buffalo

and

Erie

County

Historical

Society.27

Edlund

describes

the

three

vases,

all

common

types,

now held in

the

Historical

Society. Raymond

J. Hughes,

Curator

of

the Museum of

the

Society, provided

useful data

to

Edlund about

1980.

Although

Barrett

died

in

1903,

the

acquisition

is

reported

to have become

official

only

in

1930,

possibly

being

considered

as loans until

that

time. Since Barrett's

widow died

about

1925,

these vases

may

have remained

in her

possession

un-

til her death. If all

of the Barrett materials

remained

with

his

widow,

who suffered

various

difficulties

prior

to her

death,

the

gold appliance

or

appliances

as

well as the more valuable

items

in the collection

may

have been sold between

1903 and ca.

1925.

Aside

from the three vases

noted

by

Edlund,

all of

the other

pieces

from

this

tomb,

including

the den-

tal

appliance,

are lost.

Mildred

F.

Hallowitz,

History

of

Medicine Librarian

of

the

Health Sciences

Li-

brary

at the State

University

of New York at

Buffalo,

provided

Edlund with information

regarding

the

be-

quest

of

artifacts

to the School

of

Dentistry.

These

items

should

be

compared

with observations

made

by

Helbig.

One

item,

a bronze

situla,

has been

noted

as

possibly

in

Dresden,

but

there

may

be

some

confu-

sion

between

the

Barrett tomb

bronzes

and other

bronzes that

Helbig

notes went to

Dresden.28

The

Albright-Knox

Museum in

Buffalo now

in-

cludes

a small

collection

of

ancient artifacts. The lo-

cation

of the Museum

across the street

from

the

Erie

County

Historical

Society,

to which some of

the Bar-

rett

collection

supposedly

had been

bequeathed,

suggests

that

it should be

checked

for

Roman

or

Etrus-

can ceramics

or other items

that

may

have once

been

held

by

Barrett.

Similarly,

the enormous

warehouse

of

the Erie

County

Historical

Society,

opened

in

1990,

contains vast numbers of

boxes

that have

yet

to

be

inventoried.

One

or more

of these

three

small

Etruscan

gold

dental

appliances may

be

among

these vast

holdings.

THE

VAN

MARTER

APPLIANCE

A

third

appliance,

also

now

missing,

was

found

near the

Lake of

Valseno

(Bolseno),

near

Rome

(fig.

24

Weinberger

(supra

n.

16)

125;

also

Becker,

unpublished

manuscript

(supra

n.

7)

on

appliances

from

Tarquinia.

25

Helbig

(supra

n.

10);

see

also

Edlund

(supra

n.

11).

26

Helbig

(supra

n.

10)

26.

Helbig

refers to

"Schoell

p.

155,"

a

reference

that

I

have

been

unable

to locate.

27

Edlund

(supra

n.

11)

82.

28

Helbig

(supra

n.

10).

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1999]

ETRUSCAN GOLD

DENTAL APPLIANCES

109

Q ~~r~u~~

:? ~ tl`?

i -

:"t~CI\:Ft.

t~ ?';!(

I I , I

Fig.

4. The Van

Marter

appliance.

This

appliance

is

proba-

bly

a

maxillary prosthesis,

shown

by

Van Marter

in an

in-

verted

position.

(After

J.G.

Van

Marter,

Dental

Register

43

[1889] 261)

4).

The Van

Marter

appliance

has

three

rings

that

have

been cold-welded

into

a

series,

a

design

that is

typical

of

Etruscan

pontics.

The

only

known refer-

ence

to this

Etruscan

dental

prosthesis

has

been

"buried"

in

an obscure

publication

for over

100

years;

only

a

drawing

and brief

description

pub-

lished

by

Van

Marter

preserve

this

item for

us,

and

it

is

fitting

that this

example

be named for

him.29

Al-

though

the associated

skull

had crumbled

in the

tomb,

the

description

of the

appliance

leads

me to

believe that

it

was

a

maxillary prosthesis

(upperjaw),

and worn

by

a female.

The date of

600

B.C.

assigned

by

Van

Marter must

be considered

as

speculative.

Aside

from our

knowledge

that Van Marter

was a

friend of

Barrett's,

we know

nothing

of his

life and

training prior

to

1889. In that

year,

or

shortly

before,

Van

Marter,

then

living

in

Rome,

noted that this

den-

tal

appliance

had been

"taken from

an Etruscan

tomb

lately opened

not far from Rome

on the lake

of

Valseno." Van

Marter notes

that the three

rings

of

the

specimen

are

welded,

with no

joints

being

evi-

dent as would

be the

case

with

soldering.

Clearly

he

is

describing

a

cold-welded

Etruscan

appliance, typi-

cal

of the

type

using

a series of

rings.

The

anchor

teeth to which

this

bridge

was attached

are

not illus-

trated.

Van Marter

describes

the false

tooth,

located

in

the central

ring,

as "a

bicuspid,

turned one-fourth

round on its axis."

Although

his illustration shows

this

in

a "mandibular"

position (fig.

4),

the

"bicus-

pid,"

or

premolar, appears

to be a

large right

maxil-

lary

example.

If this were

the

case,

this

appliance

would have

bridged

the

spaces

between

the

upper

right

canine and

right

second

premolar.

This

is

a

very

unlikely

series

(replacing

a

first

premolar).

I

sus-

pect

that

the false

tooth

is

actually

meant to

replace

a

central

incisor,

and

that

the

appliance

bridged

both the other

central

and

one lateral

incisor.

From

the

illustration

it

appears

that

the

replace-

ment tooth

in

the

Van

Marter

bridge

is held

in

posi-

tion

like a

gemstone,

in a fashion similar

to that

of

an

example

in

Copenhagen,

described

below.

The

construction

of

the

Van

Marter

prosthesis

certainly

ap-

pears

similar

to

that of the

Copenhagen

bridge.

This

appliance

may

be one

of five

examples

that Dunn

noted

as

"lost,"

presumably

to

private

collections.30

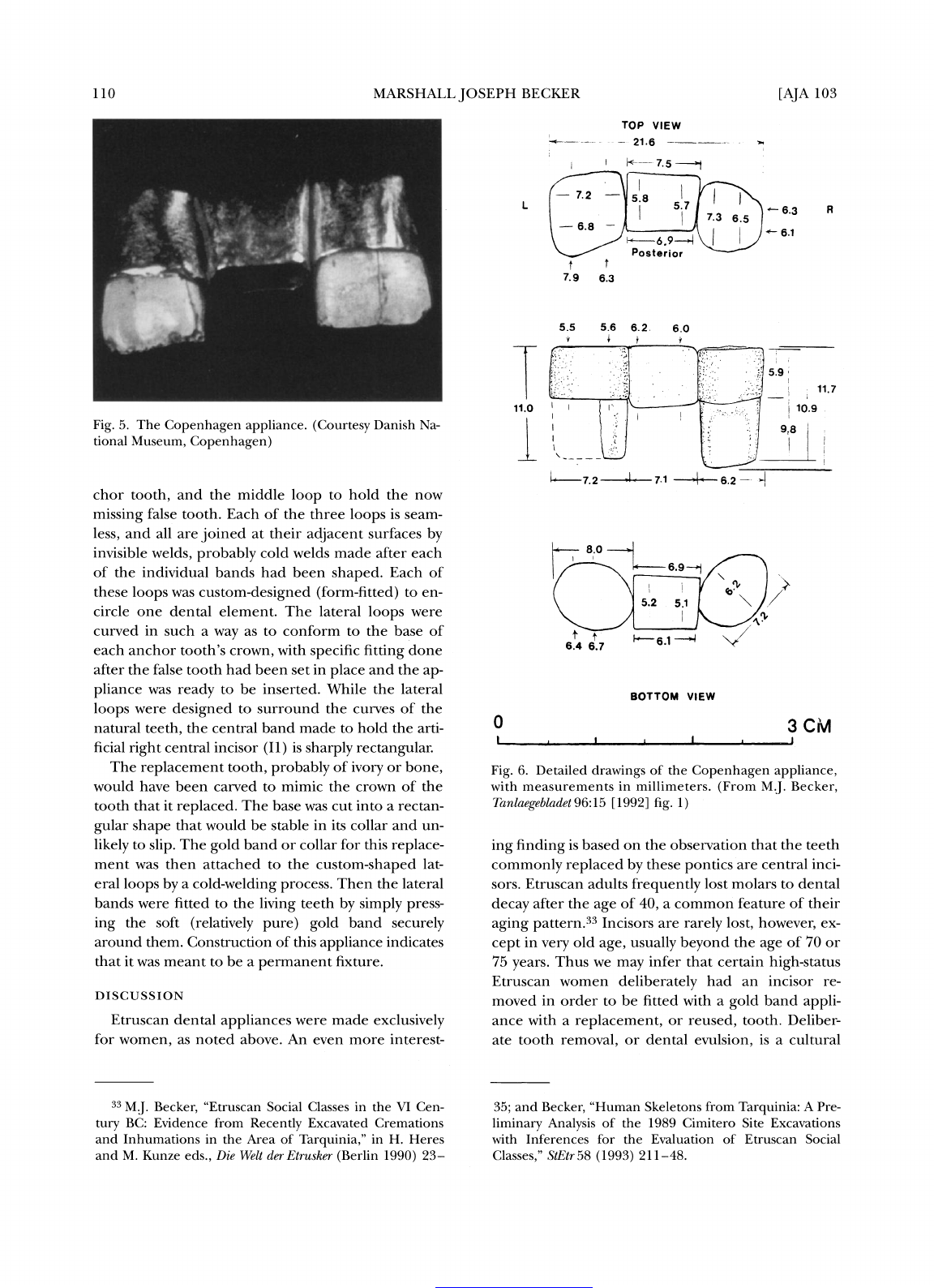

BRIEF DESCRIPTION

OF

THE

COPENHAGEN

PROSTHESIS

The

Copenhagen

prosthesis

(figs.

5-6),

in

the

Danish

National

Museum,

has

recently

been

pub-

lished

in

detail,

providing

an excellent

comparative

example

for

reconstructing

the Van

Marter

appli-

ance.31 Riis

believes

that it came

from

Orvieto,

and

associated

ceramics

appear

to indicate

a date

of

ca.

500-490

B.C.32 This

three-ring gold prosthesis

was

meant to

be worn

in the

upper

jaw

of

an adult

fe-

male. The

Copenhagen

gold

dental

prosthesis

uses

a

complex

variation of the

simple

band

technique-

that of

welding

individual

"rings"

or

small

loops

each

of which is fitted

to a

single

tooth. This

technique

is

only

one of several

known construction

variations.

The

Copenhagen

bridge

is

made of three

sepa-

rate

rings

cold-welded

together.

The

left

loop

is

fit-

ted to the

upper

left central

incisor

(11),

and the

loop

on the other

end had

been fitted to

the

right

lateral incisor

(I2).

These

teeth

served

as

the

anchor,

or

"post,"

teeth,

those sound or

living

teeth to which

the

bridge

was

attached to hold

it in

place.

The rect-

angular

central

loop

held a false tooth. No

rivet

(pin)

is

needed

in

this

type

of

bridge

since

the false

tooth had

been

held

in

place

the

way

a

gemstone

is

fixed

in

its

setting.

A

small

band was made and then

fitted

with the

false tooth

in the

same fashion

that a

goldsmith

would make

any

bezel

setting.

The rectan-

gular setting

would

prevent

rotation and facilitate

a

good

fit,

and the false tooth

would

then be

secured

in

place by pressing

the

gold tightly

as with

the

gold

of the

lateral

loops.

Three

separate

straps

or

bands

were fashioned

into

loops,

the lateral

examples

to surround an an-

29J.G.

Van

Marter,

"Prehistoric

Dentistry--Bridge

Work,"

Dental

Register

43

(1889)

261.

30

C.G.

Dunn,

L'arte

dentaria

fra gli

Etruschi

(Florence

1894).

31

Becker

1992

(supra

n.

4);

and Becker

1994,

DentalAn-

thropology

Newsletter

(supra

n.

4).

32

P.J.

Riis,

Tyrrhenika:

An

Archaeological

Study

of

the Etrus-

can

Sculpture

in the Archaic

and Classical

Periods

(Copen-

hagen

1941)

161.

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

110 MARSHALL

JOSEPH

BECKER

[AJA

103

Fig.

5.

The

Copenhagen

appliance. (Courtesy

Danish Na-

tional

Museum,

Copenhagen)

chor

tooth,

and the

middle

loop

to hold

the now

missing

false tooth. Each

of the three

loops

is seam-

less,

and all are

joined

at their

adjacent

surfaces

by

invisible

welds,

probably

cold

welds

made after each

of the

individual bands had been

shaped.

Each of

these

loops

was

custom-designed

(form-fitted)

to en-

circle one

dental element. The lateral

loops

were

curved

in

such a

way

as to conform to the base of

each anchor

tooth's

crown,

with

specific fitting

done

after

the false tooth had been set

in

place

and the

ap-

pliance

was

ready

to be inserted.

While

the lateral

loops

were

designed

to surround the curves of the

natural

teeth,

the central band made to hold the arti-

ficial

right

central incisor

(11)

is

sharply

rectangular.

The

replacement

tooth,

probably

of

ivory

or

bone,

would have been carved to mimic the crown of

the

tooth that it

replaced.

The base

was

cut into a rectan-

gular shape

that

would

be stable

in

its collar and un-

likely

to

slip.

The

gold

band or collar for

this

replace-

ment

was then attached to the

custom-shaped

lat-

eral

loops

by

a

cold-welding process.

Then the lateral

bands were fitted to the

living

teeth

by simply press-

ing

the soft

(relatively pure) gold

band

securely

around them. Construction of this

appliance

indicates

that

it was meant to be a

permanent

fixture.

DISCUSSION

Etruscan dental

appliances

were made

exclusively

for

women,

as

noted above.

An

even more interest-

ing finding

is based on the observation that the teeth

commonly replaced by

these

pontics

are

central inci-

sors. Etruscan adults

frequently

lost

molars to dental

decay

after the

age

of

40,

a common feature

of

their

aging pattern.33

Incisors are

rarely

lost, however,

ex-

cept

in

very

old

age, usually beyond

the

age

of 70 or

75

years.

Thus we

may

infer that certain

high-status

Etruscan women

deliberately

had an

incisor re-

moved

in

order to

be fitted

with

a

gold

band

appli-

ance with a

replacement,

or

reused,

tooth. Deliber-

ate

tooth

removal,

or dental

evulsion,

is a cultural

TOP VIEW

-

21.6

---

7.5

----8

L

5.7

76.3

R

7.3

6.5

6.8

6.1

Posterior

t

t

7.9

6.3

5.5 5.6

6.2

6.0

11.7

9.8

-7.2

7.1

6.2--

8.o

6.9

5.2

5.1

t

6.1

6.4

6.7

BOTTOM VIEW

0

31CM

I

I

I

Fig.

6. Detailed

drawings

of the

Copenhagen appliance,

with measurements

in

millimeters.

(From

M.J.

Becker,

Tanlaegebladet

96:15

[1992]

fig.

1)

33

M.J.

Becker,

"Etruscan Social Classes

in

the VI Cen-

tury

BC:

Evidence from

Recently

Excavated Cremations

and

Inhumations

in

the Area of

Tarquinia,"

in

H. Heres

and

M.

Kunze

eds.,

Die Welt der Etrusker

(Berlin

1990)

23-

35;

and

Becker,

"Human Skeletons from

Tarquinia:

A

Pre-

liminary Analysis

of the

1989

Cimitero Site Excavations

with Inferences for the Evaluation of Etruscan Social

Classes,"

StEtr58

(1993)

211-48.

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1999]

ETRUSCAN GOLD DENTAL APPLIANCES

pattern

known from

many

areas in

antiquity,

includ-

ing Italy,

that survives

in

many parts

of the

world

to-

day.34

That this

cultural

pattern

of

tooth removal

and elaborate

replacement

with

gold fittings

was

part

of

the southern Etruscan cultural tradition

is

strongly

indicated

by

the distribution of

these

finds

as

well as

the

decline

in

their use as Etruscan

cities,

writing,

and

culture

were absorbed into

the

growing

Roman

empire.

DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY

WEST

CHESTER UNIVERSITY

OF

PENNSYLVANIA

WEST

CHESTER,

PENNSYLVANIA

19383

34J.

Robb,

"Intentional Tooth

Removal

in

Neolithic Ital-

ian

Women,"

Antiquity

71

(1997)

659-69;

and

M.J.

Becker,

"Tooth

Evulsion

among

the Ancient

Etruscans,"

Dental An-

thropology

Newsletter9:3

(1995)

8-9.

This content downloaded from 144.26.117.20 on Thu, 14 May 2015 18:13:01 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions