HOUSING

NOT

HANDCUFFS

2019

December 2019

Ending the Criminalization of

Homelessness in U.S. Cities

2

The National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty (Law Center) is the only national organization

dedicated to using the power of the law to end and prevent homelessness. The Law Center works to expand

access to affordable housing, meet the immediate and long-term needs of those who are homeless or at

risk, and strengthen the social safety-net through policy advocacy, public education, impact litigation, and

legal training and support.

Our vision is for an end to homelessness in America. A home for every family and individual will be the

norm and not the exception, a right and not a privilege. For more information about the Law Center and

to access publications such as this report, please visit its website at www.nlchp.org.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER: The information provided in this publication is not legal advice and should not be

used as a substitute for seeking professional legal advice. It does not create an attorney-client relationship

between the reader and the Law Center.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL LAW CENTER

ON HOMELESSNESS & POVERTY

LAW CENTER BOARD OF DIRECTORS

LAW CENTER STAFF

Eric A. Bensky, Chair

Murphy & McGonigle PC

Julia M. Jordan, Vice-Chair

Sullivan & Cromwell LLP

Kirsten Johnson-Obey, Secretary

NeighborWorks

Robert C. Ryan, Treasurer

American Red Cross

Paul F. Caron

Microsoft Corporation

Bruce J. Casino

Attorney

Rajib Chanda

Simpson, Thacher, & Bartlett LLP

Dwight A. Fettig

Porterfi eld, Fettig & Sears, LLC

Deborah Greenspan

Blank Rome LLP

Steve Judge

Private Equity Growth Capital Council

(Retired)

Georgia Kazakis

Covington & Burling LLP

Pamela Malester

Offi ce for Civil Rights, U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services

(Retired)

Edward R. McNicholas

Ropes & Gray LLP

Tashena Middleton

Attorney

Matthew Murchison

Latham & Watkins LLP

G.W. Rolle

Missio Dei Church

Jeffrey A. Simes

Goodwin Procter LLP

Vasiliki Tsaganos

Franklin Turner

McCarter & English LLP

Robert Warren

People for Fairness Coalition

Khadijah Williams

Rocketship Public Schools

Maria Foscarinis

Founder & Executive Director

*Affi liations for identifi cation

purposes only

Rajan Bal

Housing Not Handcuffs Campaign

Manager

Karianna Barr

Director of Development &

Communications

Tristia Bauman

Senior Attorney

Maria Foscarinis

Founder & Executive Director

Jordan Goldfarb

Development & Communications

AmeriCorps VISTA

Crys Letona

Communications Associate

Kelly Miller

Development & Communications

Volunteer

Brandy Ryan

Staff Attorney

Deborah Shepard

Operations Manager

Eric Tars

Legal Director

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty is grateful to the following individuals and

fi rms for their tremendous contributions to the research, writing, and layout of the report:

Law Center staff, fellows, and interns past and present, especially Tristia Bauman for serving as primary

author and editor; Rajan Bal, Karianna Barr, Maria Foscarinis, Brandy Ryan, and Eric Tars for drafting

and editing; Taylor de Laveaga, Joy Kim, Darren O’Connor, and Scott Pease for research and drafting

support; Crys Letona for design.

Dechert LLP, Kirkland & Ellis LLP, and Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, who committed staff and pro bono hours to

researching and updating the Prohibited Conduct Chart.

We also acknowledge with gratitude the generous support of the Oak Foundation, the Oakwood

Foundation, and the Herb Block Foundation. The Law Center would also like to thank AmeriCorps VISTA

for its support.

The Law Center woul

d like to thank our Lawyers’ Executive Advisory Partners (LEAP) member law fi rms:

Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP; Arent Fox LLP; Baker Donelson PC; Covington & Burling LLP; Dechert

LLP; Fried, Frank, Harris; Goldman Sachs and Co. LLC; Goodwin Procter LLP; Kirkland & Ellis LLP; Latham

& Watkins LLP; McCarter & English LLP; Microsoft Corporation; Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP;

Sidley Austin LLP; Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP; Sullivan & Cromwell LLP; and WilmerHale.

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND ON THE AFFORDABLE HOUSING CRISIS AND THE

RISE OF HOMELESSNESS

INTRODUCTION

Homelessness is a large and growing crisis

The gap between incomes and the cost of housing is a primary cause of homelessness

People of color face disproportionate housing cost burdens, eviction, and homelessness

People with disabilities are also disproportionately homeless

People experiencing homelessness have insuffi cient options for meeting their basic human needs

GROWTH OF LAWS CRIMINALIZING HOMELESSNESS

Camping Bans

Evictions of Encampments (“Sweeps”)

Sleeping Bans

Bans on Sitting and Lying Down

Restrictions on Living in Vehicles

Begging Bans

Bans on Loitering, Loafi ng, and Vagrancy

Restrictions on Food Sharing

Other Common Criminalization Laws

Storing personal property in public

Urination/Defecation

Rummaging/Scavenging/Dumpster Diving

Laws Criminalizing Homeless Youth

Status Offenses

Curfew Laws

Truancy Laws

ENFORCEMENT OF CRIMINALIZATION POLICIES

Arrest and Incarceration

Fines, Fees, and Debtors Prison

Warrants

Orders to “Move Along” from Public Space

9

11

27

28

29

32

33

33

37

38

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

46

48

50

50

52

52

53

TABLE OF CONTENTS

6

Privatization of Public Space

Hostile Architecture and Landscaping

Complaint Oriented Policing

HALL OF SHAME

Ocala, Florida

Sacramento, California

Wilmington, Delaware

Kansas City, Missouri

Redding, California

State of Texas

U.S. Government

CRIMINALIZING HOMELESSNESS PERPETUATES UNFOUNDED AND HARMFUL

STEREOTYPES ABOUT HOMELESS PEOPLE

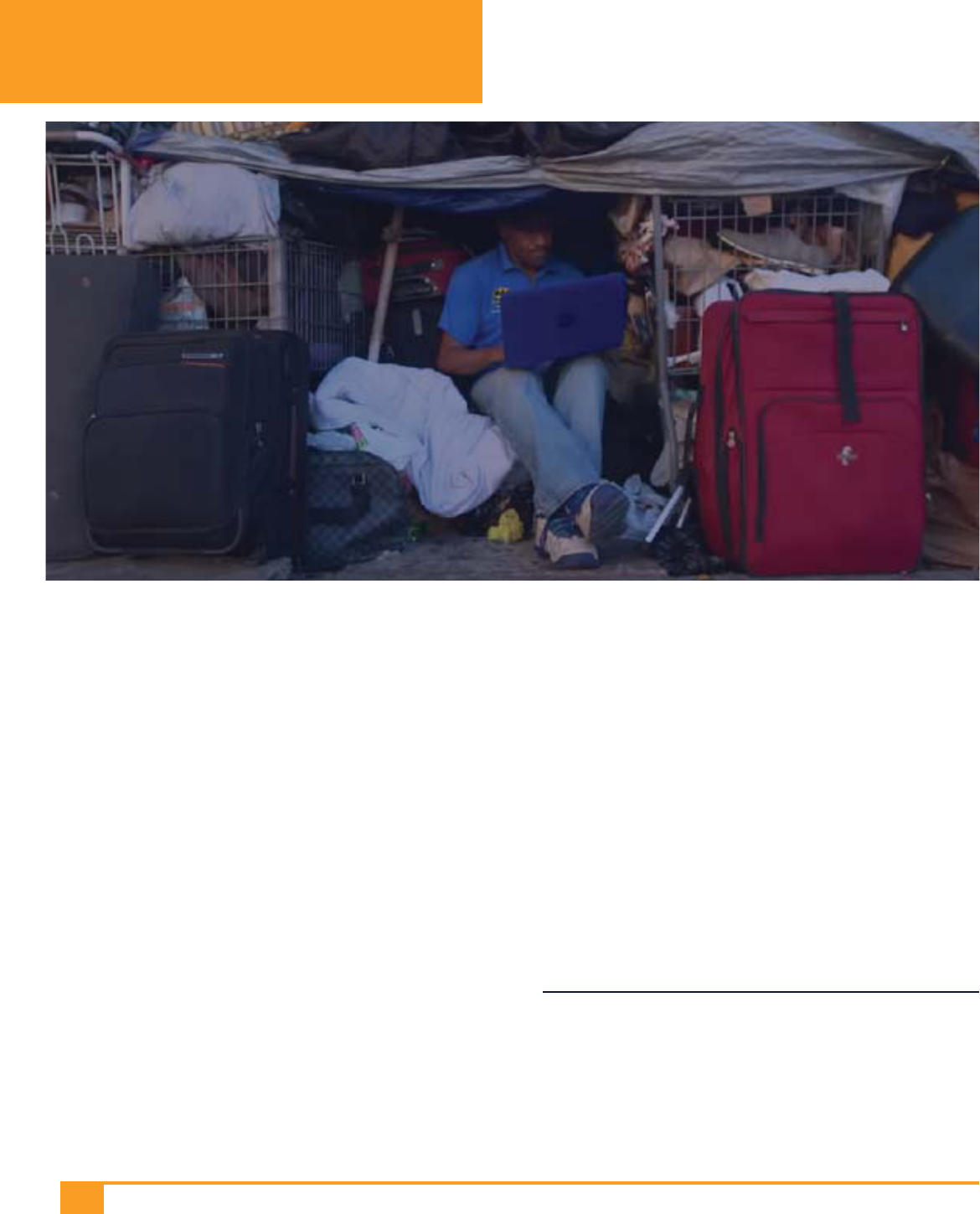

Homeless people live outside because they lack better options

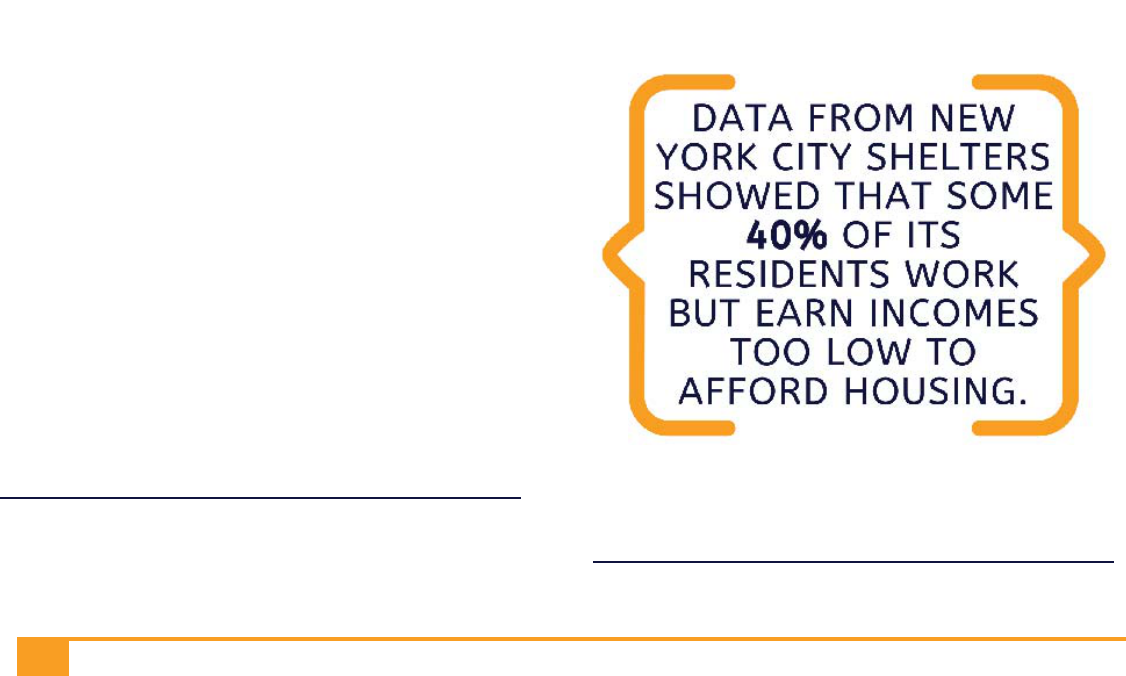

Homeless people work, but still cannot afford housing

The vast majority of homeless people do not abuse alcohol and/or drugs

CRIMINALIZING HOMELESSNESS IS INEFFECTIVE, HARMFUL, AND EXPENSIVE PUBLIC

POLICY

Criminalization policies fail to address the causes of homelessness, and instead

worsen the problem

Criminalization of homelessness harms public safety

Criminalization laws harm public health

Criminalization increases recidivism

Criminalization policies breed distrust between homeless individuals and law enforcement

Criminalization policies increase the risk of violence against homeless people

Criminalization is expensive and wasteful of limited public resources

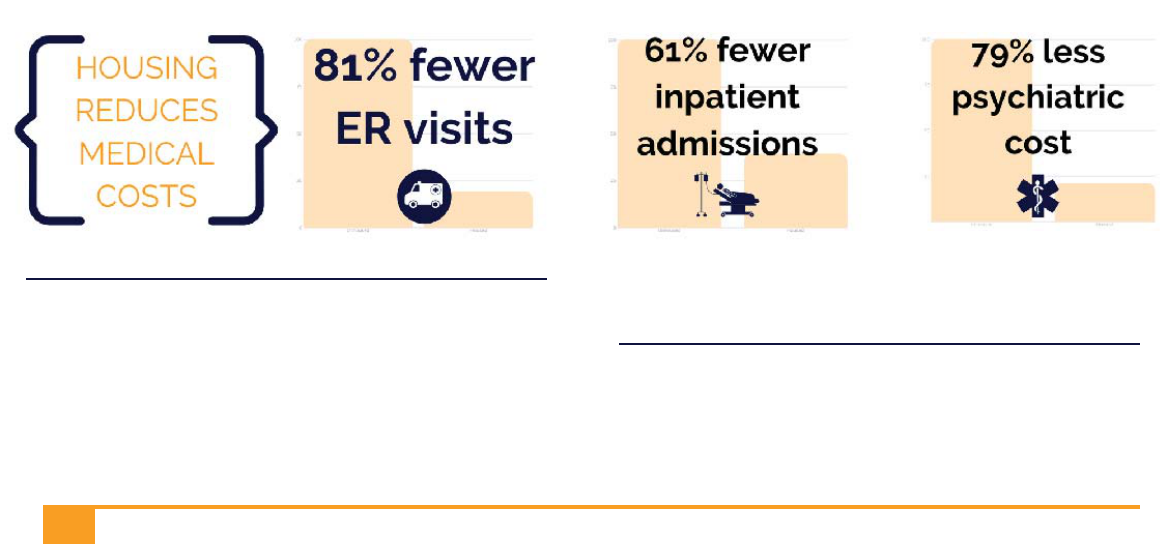

The solution is cheaper than the problem

Cost savings associated with housing are grossly underestimated

Housing saves money by improving physical and mental health

Criminalization policies threaten federal funding for homeless services

53

54

56

57

60

60

61

62

63

63

65

67

71

73

TABLE OF CONTENTS

7

POLICIES CRIMINALIZING HOMELESSNESS ARE OFTEN ILLEGAL

Challenging Camping and Sleeping Bans and Sweeps

Right to be Free From Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Property Rights and Due Process

Right to Free Exercise of Religion

Challenging Restrictions on Living in Vehicles

Right to Due Process

Other Theories to Challenge Vehicle Tows and Impoundment

Challenging Loitering, Loafi ng, and Vagrancy Laws

Challenging Begging Bans

Right to Free Speech

Challenging Food Sharing Restrictions

Right to Free Religious Exercise

Right to Expressive Conduct

Challenging the Human Rights Violations of Criminalization

WE SHOULD SOLVE HOMELESSNESS, NOT PUNISH IT

Cities should invest in Permanent Housing Solutions using a Housing First model

Permanent Supportive Housing

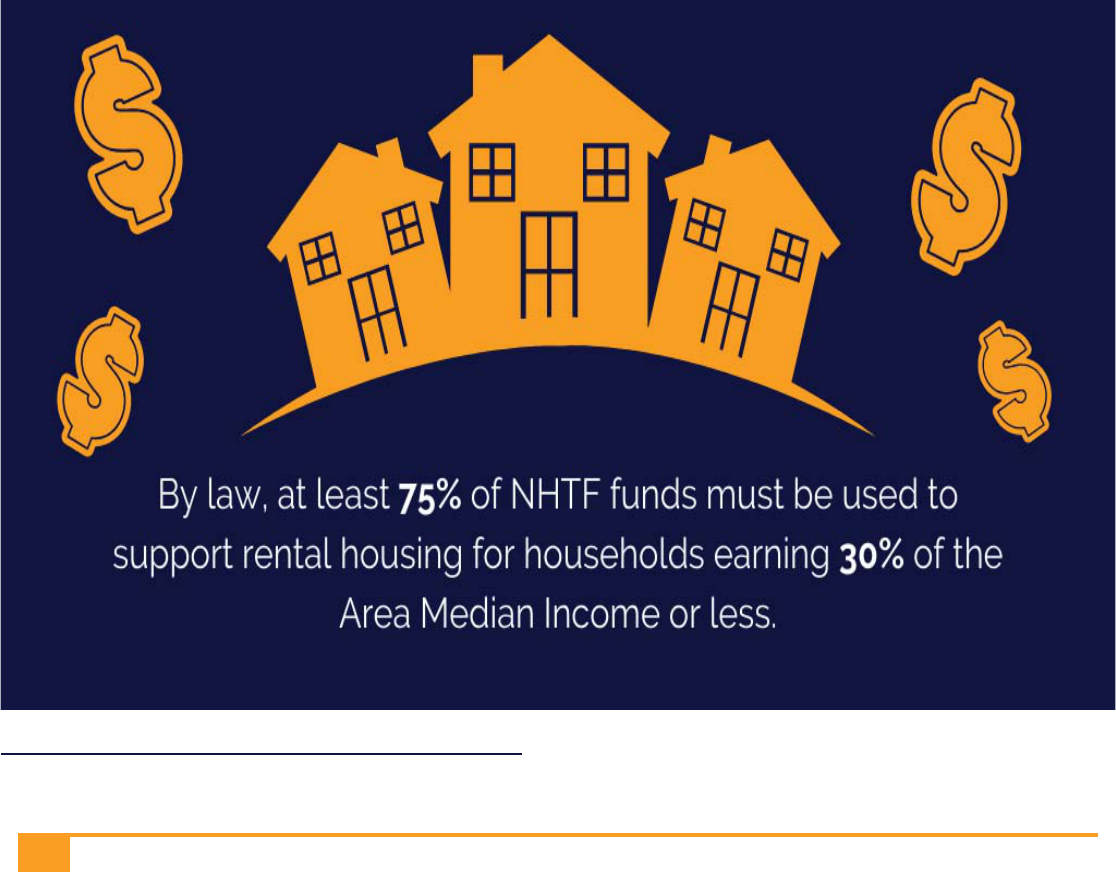

Governments should expand access to affordable housing subsidies

Governments should dedicate funding streams to housing and services for homeless people.

Tax on gross receipts of large companies

Sales Tax

Social Impact Bonds

Solicit Corporate and Private Donations

Governments should utilize surplus property to provide housing and services

Governments should embrace innovative housing solutions

Accessory Dwelling Units

Tiny Home Communities

Community Land Trusts

Vehicle and RV Parking Options

75

75

79

80

80

81

81

85

85

87

89

90

91

92

TABLE OF CONTENTS

8

Governments should stop using punitive approaches to homelessness

Repeal, defund, and stop enforcing laws that criminalize homelessness

Prohibit the criminalization of homelessness through legislation

Stop sweeping encampments without offering adequate alternatives

Stop relying on police to be fi rst responders to homelessness

Improve police training and enforcement protocols

Governments should help homeless people meet basic human needs until housing is available.

Establish places where people can store their property

Provide access to toilets

Provide unhoused people with trash services

Provide people with shower and laundry services

Help people meet their need for shelter from the elements

Low-Barrier Emergency Shelters

Authorized Encampments

Safe Parking Lots

Help people access income

Governments should enact policies tailored to homeless youth needs

Governments should prevent homelessness before it happens

Enact “Just Cause” eviction protections and rent stabilization laws

Prohibit discriminatory housing policies

Guarantee a right to counsel in housing cases

CONCLUSION

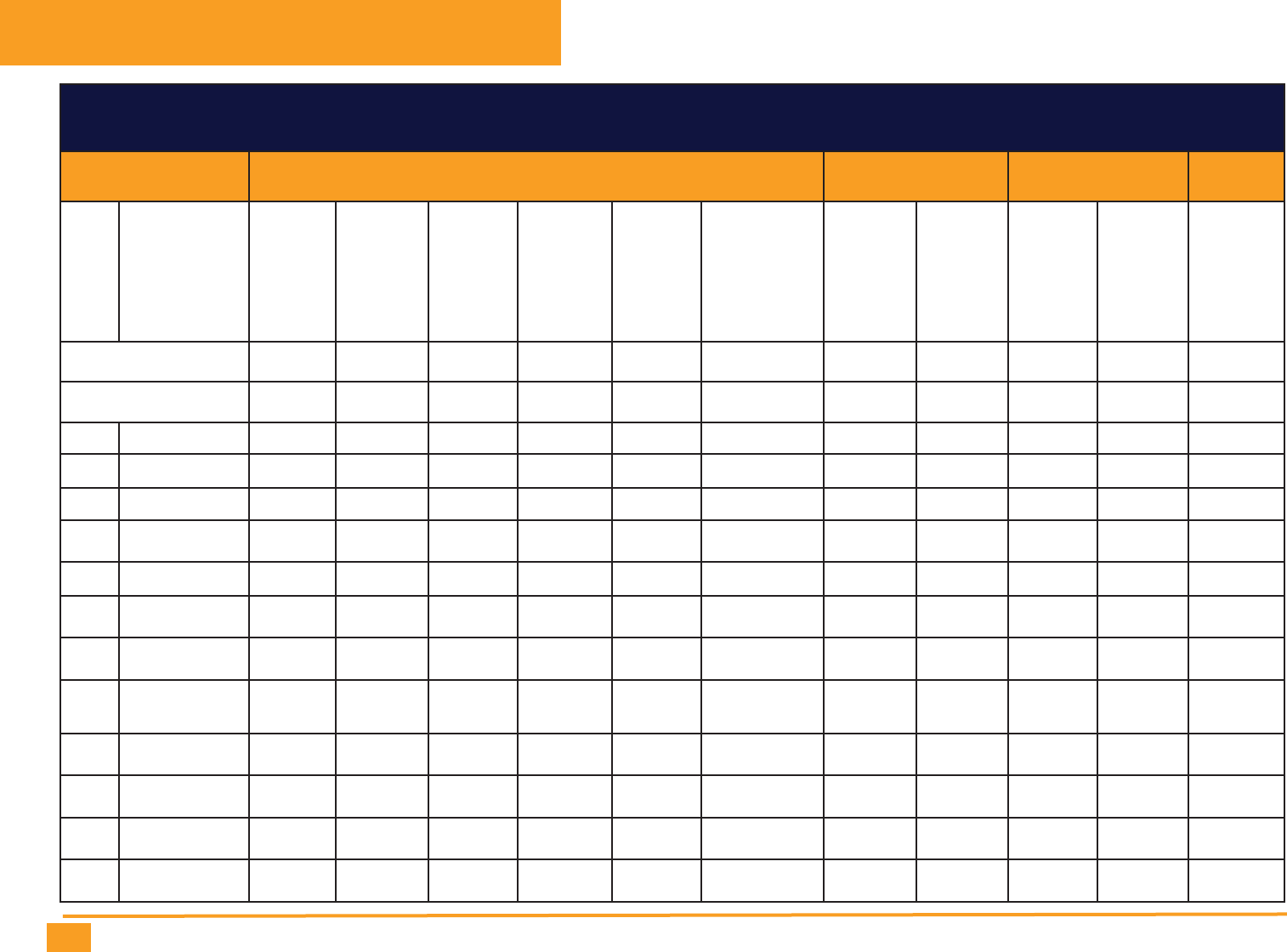

Appendix A: Prohibited Conduct Chart by City

Appendix B: Encampment Principles and Best Practices

95

98

100

102

103

105

106

119

H

ousing is a human right. While three-quarters of Americans agree that housing is a human right, and an increasing

number of elected offi cials are addressing it as such, our country has not put in place the policies to ensure that

right, and as a consequence, millions of Americans experience homelessness in a national crisis that gets worse

each year. Many people experiencing homelessness have no choice but to live outside, yet cities routinely punish or harass

unhoused people for their presence in public places. Nationwide, people without housing are ticketed, arrested, and jailed

under laws that treat their life-sustaining conduct—such as sleeping or sitting down—as civil or criminal offenses. In addition,

cities routinely displace homeless people from public spaces without providing any permanent housing alternatives.

This report—the only national report of its kind—provides an overview of laws in effect across the country that punish

homelessness. With the assistance of the law fi rms Dechert LLP, Sullivan & Cromwell, and Kirkland & Ellis, the Law Center

examined the city codes of 187 urban and rural cities across the country. Through online research, we identifi ed laws that

restrict or prohibit different categories of conduct performed by homeless people, including sleeping, sitting or lying down,

and living in vehicles within public space. We refer to these policies and their enforcement collectively as the “criminalization

of homelessness,” even though these laws are punishable as both criminal and civil offenses.

The ordinances from our research group of 187 cities are listed in our Prohibited Conduct Chart in Appendix A. While the

chart catalogues the existence of these laws in different cities, actual enforcement of them may vary widely. Punishments also

9

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

10

vary: some laws subject homeless people to as much as six months in jail, while some result in expensive fi nes, fees, and/

or displacement from public space. Threats of enforcement are also used to harass homeless people and to displace them

from location to location. It is important to note that these 187 cities are only a sampling; criminalization ordinances exist in

many more municipalities than just the ones covered here.

In addition to our survey of policies in force across the country, this report describes trends in criminalization laws and tracks

the signifi cant growth of these laws since we began tracking them thirteen years ago, and since the release of Housing Not

Handcuffs, our last report on the criminalization of homelessness in 2016.

1

This report also describes why criminalization

policies are ineffective, harmful, expensive to taxpayers, and often even illegal.

Because our end goal is not to protect the right to live on the streets, but rather to ensure that people need not live

without housing in the fi rst place, we also offer constructive alternative approaches to preventing and ending homelessness.

Included in our recommendations are model policies for federal, state, and local governments to address homelessness in

a cost-effective, humane, and legal way.

1 NAT’L L. CTR. ON HOMELESSNESS & POVERTY, HOUSING NOT HANDCUFFS: ENDING THE CRIMINALIZATION OF HOMELESSNESS IN U.S. CITIES (2016),

https://nlchp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Housing-Not-Handcuffs.pdf.

THE AFFORDABLE HOUSING CRISIS AND

THE GROWTH OF HOMELESSNESS

Rising rents, stagnant wages, historically low rental

vacancy rates, and the severe decline of federally

subsidized housing have led to a critical shortage of

affordable housing units. There is simply not enough

affordable and available housing for America’s millions of

low-income renters, leaving them at risk of homelessness.

Nationwide, there are only 35 units that are affordable and

available for every 100 extremely poor renter households

in need. The affordable housing gap is even more severe

in many of the nation’s large metropolitan areas. The result

is that low-income renter households are housing cost

burdened, meaning they are forced to pay more than they

can sustainably afford toward rent.

Housing cost burdens and eviction cause homelessness.

Recent studies have demonstrated the strong connection

between rental costs, housing cost burdens, and

homelessness. For example, one study predicted that

homelessness in New York City would increase by over

6,000 people if rents increase by 10%. Unaffordable rents

result in evictions for non-payment of rent, even after a

single late or missed payment. Eviction is not only a direct

cause of homelessness, a record of eviction can also bar

someone from becoming rehoused.

Housing cost burdens and eviction have contributed

to grossly disproportionate rates of homelessness

among people of color. People of color make up the

majority of housing cost burdened renters at risk of eviction,

and once housing is lost, racist housing practices prevent

people from becoming rehoused. It is thus unsurprising

that there is a heavy overrepresentation of people of color

in the homeless population. According to HUD’s most

recent point-in-time count, Black people make up 40%

of the homeless population yet only 13% of the general

population. Latinx, Native American, and Pacifi c Islander

rates of homelessness are also disproportionately high. In

total, people of color constitute over 60% of the nation’s

homeless population even though they make up only a third

of the general U.S. population.

People without housing lack options for meeting

their basic human needs for rest and shelter. Many

communities treat emergency shelters as the answer

to systemic shortages of permanent housing, and they

often justify enforcement of criminalization laws based

on alleged availability of emergency shelter beds. But

emergency shelters are not available in every community

with unhoused people, and even where shelters exist, they

are generally full and routinely turn people away at the front

door. Moreover, emergency shelters offer only temporary

shelter—sometimes only for a single night at a time—and

frequently require that people separate from their families,

beloved pets, and/or their property upon entry, or subject

themselves to religious proselytizing. Shelters may also

discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender

identity, and/or fail to accommodate disability needs.

KEY FINDING: The criminalization of homelessness

is on the rise. The results of our research show that the

criminalization of homelessness is prevalent across the

country and has increased in every measured category

since 2006, when the Law Center began tracking these

policies nationwide. We also found a growth in laws

criminalizing homelessness since the release of our last

Housing Not Handcuffs report, released in 2016.

11

BACKGROUND

Punishing homelessness has

increased over the last 13 years.

Of the 187 cities measured by the Law Center, we found:

LAWS PROHIBITING CAMPING IN PUBLIC

“Camping” bans are often written to cover a broad range

of activities, including merely sleeping outside. They also

often prohibit the use of any “camping paraphernalia”

which can make it illegal for unhoused people to use even

a blanket. In 2019, 72% of our 187 surveyed cities have

at least one law restricting camping in public. Among our

surveyed cities:

• 37% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

camping citywide.

• 57% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

camping in particular public places.

• Both categories have signifi cantly increased over the

past 13 years:

• Since 2006, 33 new laws prohibiting camping

citywide were enacted, representing a 92%

increase. Since we released our last national report

on the criminalization of homelessness in 2016, nine

such laws were enacted, representing an increase

of 15%.

• Since 2006, 44 new laws prohibiting camping in

particular places were enacted, representing a 70%

increase. Since 2016, 14 such laws were enacted,

representing a 15% increase.

12

LAWS PROHIBITING SLEEPING IN PUBLIC

Sleeping bans outlaw sleep, which cannot be foregone

by any human being. In 2019, 51% of our 187 surveyed

cities have at least one law restricting sleeping in public.

Among our surveyed cities:

• 21% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

sleeping in public citywide.

• 39% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

sleeping in particular public places.

• Both categories have signifi cantly increased over the

past 13 years:

• Since 2006, 13 new laws prohibiting sleeping

citywide were enacted, representing a 50%

increase. Since we released our last national report

on the criminalization of homelessness in 2016, six

such laws were enacted, representing an increase

of 18%.

• Since 2006, 16 new laws prohibiting sleeping in

particular places were enacted, representing a 29%

increase. Since 2016, 22 such laws were enacted,

representing a 44% increase.

72% of cities have at least one

law prohibiting camping in

public.

City laws prohibiting

sleeping in public have

increased 50% since 2006.

13

LAWS RESTRICTING SITTING AND LYING

DOWN IN PUBLIC

Although every human being must occasionally rest, laws

restricting sitting and lying down in public punish people

experiencing homelessness for doing so. Of the 187 cities

surveyed for this report, our 2019 research reveals that:

• 55% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting sitting

and/or lying down in public.

• Such laws have signifi cantly increased over the past

13 years:

• Since 2006, 45 new laws prohibiting sitting and/

or lying down in public were enacted, representing

a 78% increase. Since we released our last national

report on the criminalization of homelessness in

2016, 15 such laws were enacted, representing a

17% increase.

LAWS PROHIBITING LOITERING, LOAFING,

AND VAGRANCY

Similar to historical Jim Crow, Anti-Okie, and Ugly laws,

these modern-day versions of those discriminatory

ordinances grant police a broad tool for excluding visibly

poor and homeless people from public places.

• 35% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

loitering, loafi ng, and/or vagrancy citywide.

• 60% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

loitering, loafi ng, and/or vagrancy in particular public

places.

• Such laws have signifi cantly increased over the past

13 years:

• Since 2006, 33 new laws prohibiting loitering,

loafi ng, and/or vagrancy citywide were enacted,

representing a 103% increase. Since we released

our last national report on the criminalization of

homelessness in 2016, six such laws were enacted,

representing an increase of 10%.

• Since 2006, 25 new laws prohibiting loitering,

loafi ng, and/or vagrancy in particular places were

enacted, representing a 28% increase. Since 2016,

13 such laws were enacted, representing a 13%

increase.

LAWS PROHIBITING BEGGING

In the absence of employment opportunities or other

sources of income, begging may be a homeless person’s

best option for obtaining the money that they need to

purchase food, public transportation fare, medication,

or other necessities. In 2019, 83% of our 187 surveyed

cities have at least one law restricting begging in public.

Among our surveyed cities:

• 38% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

begging citywide.

• 65% of cities have one or more laws prohibiting

begging in particular public places, making it the most

common type of criminalization law.

• Such laws have signifi cantly increased over the past

13 years:

• Since 2006, 36 new laws prohibiting begging

citywide were enacted, representing a 103%

increase. Since we released our last national report

on the criminalization of homelessness in 2016, 21

such laws were enacted, representing an increase

of 42%.

• Since 2006, 14 new laws prohibiting begging

There has been a 103%

increase in city laws

prohibiting loitering,

loafi ng, and/or vagrancy

since 2006.

/

or vagranc

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

2006.

14

in particular places were enacted, representing a

13% increase. Since 2016, eight such laws were

enacted, representing a 7% increase.

LAWS RESTRICTING LIVING IN VEHICLES

Sleeping in one’s own vehicle is often a last resort for

people who would otherwise be forced to sleep on the

streets. Laws restricting living in vehicles often outlaw that

activity outright, but it is also common for these laws to take

the form of parking regulations that leave no lawful place

for people who live in their vehicles to park.

• 50% of cities have one or more laws restricting living

in vehicles.

• Such laws have signifi cantly increased over the past

13 years:

• Since 2006, 64 new laws restricting living in

vehicles were enacted, representing a 213%

increase. Since we released our last national report

on the criminalization of homelessness in 2016, 22

such laws were enacted, representing an increase

of 31%.

In addition to categories of prohibited conduct studied

by the Law Center since 2006, we have more recently

tracked additional categories of prohibited conduct. Our

research shows that the following categories of laws are

also prevalent in our 187 surveyed cities:

LAWS RESTRICTING FOOD SHARING

9% of cities prohibit or restrict sharing free food in public.

People experiencing homelessness often lack reliable

access to food, in part due to a lack of any place to

refrigerate or store food supplies. Despite the fact that food

access is extremely limited for homeless people, a growing

number of cities have restricted free food sharing. Since

2016, fi ve new laws restricting food sharing were enacted,

representing an 42% increase.

LAWS PROHIBITING PROPERTY STORAGE

55% of cities prohibit storing property in public places.

People experiencing homelessness often have no private

place to secure their personal possessions. Laws that prohibit

storing property in public space leave homeless people

at constant risk of losing their property, including property

needed for shelter, treatment of medical conditions, and

proof of identity.

LAWS PROHIBITING PUBLIC URINATION AND

D

EFECATION

83% of cities prohibit public urination and defecation.

People experiencing homelessness often lack access

to toilets, yet all human beings must expel bodily waste

when nature calls—often multiple times each day. Despite

this, the vast majority of cities prohibit public urination and

defecation even in the absence of public toilets. While cities

have a legitimate interest in preventing the accumulation

of urine and feces in public space, such interests cannot

be met by criminalizing unavoidable bodily functions. If

people do not have regular access to toilets, they will expel

their human waste in areas other than toilets—they have no

choice.

LAWS PROHIBITING SCAVENGING

76% of cities prohibit rummaging, scavenging, or “dumpster

diving.” People experiencing homelessness are under

resourced, and they may turn to scavenging in trash bins

or other refuse for items of value, such as usable clothing

or edible food. Yet, three in four cities prohibit scavenging.

60.4%

of surveyed cities

have one or more laws

restricting living in

vehicles.

15

KEY FINDING: Laws criminalizing homelessness

are rooted in prejudice, fear, and misunderstanding,

and serve businesses and housed neighbors over

the needs of unhoused neighbors. It is critical

for lawmakers, policy advocates, and other key

stakeholders to understand the fundamental roots of laws

criminalizing homelessness: ignorance of the causes of

homelessness and deep-seated prejudice against and

fear of people experiencing it. The inaccurate belief

that homelessness is a result of poor life choices, mental

illness, and/or drug addiction motivates public calls for

punitive approaches to homelessness. Businesses and

commercial entities also drive criminalization policies

by lobbying for such laws and even by enforcing them

with private security personnel.

KEY FINDING: The effects of criminalization are devasting to people and communities. Criminalization

of homelessness contributes to mass incarceration and racial inequality, as homelessness is a risk factor for

incarceration, and incarceration makes it more likely that a person will experience homelessness. Over-policing of

homeless people, who are disproportionately people of color, also exacerbates racial inequality in our criminal

justice system. Indeed, unhoused people of color are more likely to be cited, searched, and have property taken

than white people experiencing homelessness. Those with multiple marginalized identities, like LGBTQ+ people of

color, are even more vulnerable to homelessness and laws criminalizing homelessness.

Criminalization of homelessness results in fines and fees that perpetuate the cycle of poverty. Financial

obligations, such as from fines for using a tent or vehicle to shelter oneself, can prolong the amount of time

that a person will experience homelessness, and can also leave homeless people less able to pay for food,

transportation, medication, or other necessities. Civil and court-imposed fines and fees can also prevent a person

from being accepted into housing, or even result in their incarceration for failure to pay them.

Criminalization of homelessness harms public safety. Criminalization policies divert law enforcement resources

from true street crime, clog our criminal justice system with unnecessary arrests, and fill already overcrowded jails.

They also erode trust between homeless people and police, heightening the risk of violent confrontations between

police and unhoused people, and leaving homeless people more vulnerable to private acts of violence without

police protection. This is why the federal Department of Justice has filed statement of interest briefs and issued

guidance arguing against the enforcement of criminalization ordinances in the absence of adequate alternatives.

Criminalization of homelessness and encampment evictions harm public health. City offi cials frequently cite concerns

for public health as reason to enforce criminalization laws and/or to evict homeless encampments, a practice often referred

to as a “sweep.” But such practices threaten public health by dispersing people who have nowhere to discard food waste

and trash, to expel bodily waste, or to clean themselves and their belongings to more areas of the city, but with no new

services to meet their basic sanitation and waste disposal needs. Moreover, sweeps often result in the destruction of

homeless people’s tents and other belongings used to provide some shelter from the elements, cause stress, and cause

loss of sleep, contributing to worsened physical and mental health among an already vulnerable population. Due to these

harms, the American Medical Association and American Public Health Association have both condemned criminalization

and sweeps in policy resolutions.

16

KEY FINDING: Criminalization isn’t just harmful,

it is ineffective, costly, and often illegal. Laws

punishing homelessness are ineffective at reducing

homelessness—they do not address underlying causes

of homelessness like the lack of affordable housing.

Instead, criminalization laws exacerbate homelessness

by creating barriers to housing, employment, and

services needed and these barriers to income and

housing can prolong a person’s homelessness or even

make it permanent.

Criminalization also wastes taxpayer dollars, taking

away resources that could be used on real solutions.

While cities often claim that proposed criminalization

measures will have no fiscal impact, the truth is that the

public costs of punitive approaches to homelessness

are staggering. A 2019 study of Santa Clara County,

California, estimated that homelessness cost Santa

Clara County $520 million annually from 2007 to 2012

(not including spending on accommodation and direct

services), and 34% of those costs were for criminal

justice related expenditures, such as probation, custody

mental health care, and jail/court costs. Sweeps are

also incredibly expensive—Los Angeles, for example,

spends $30 million a year on sweeps.

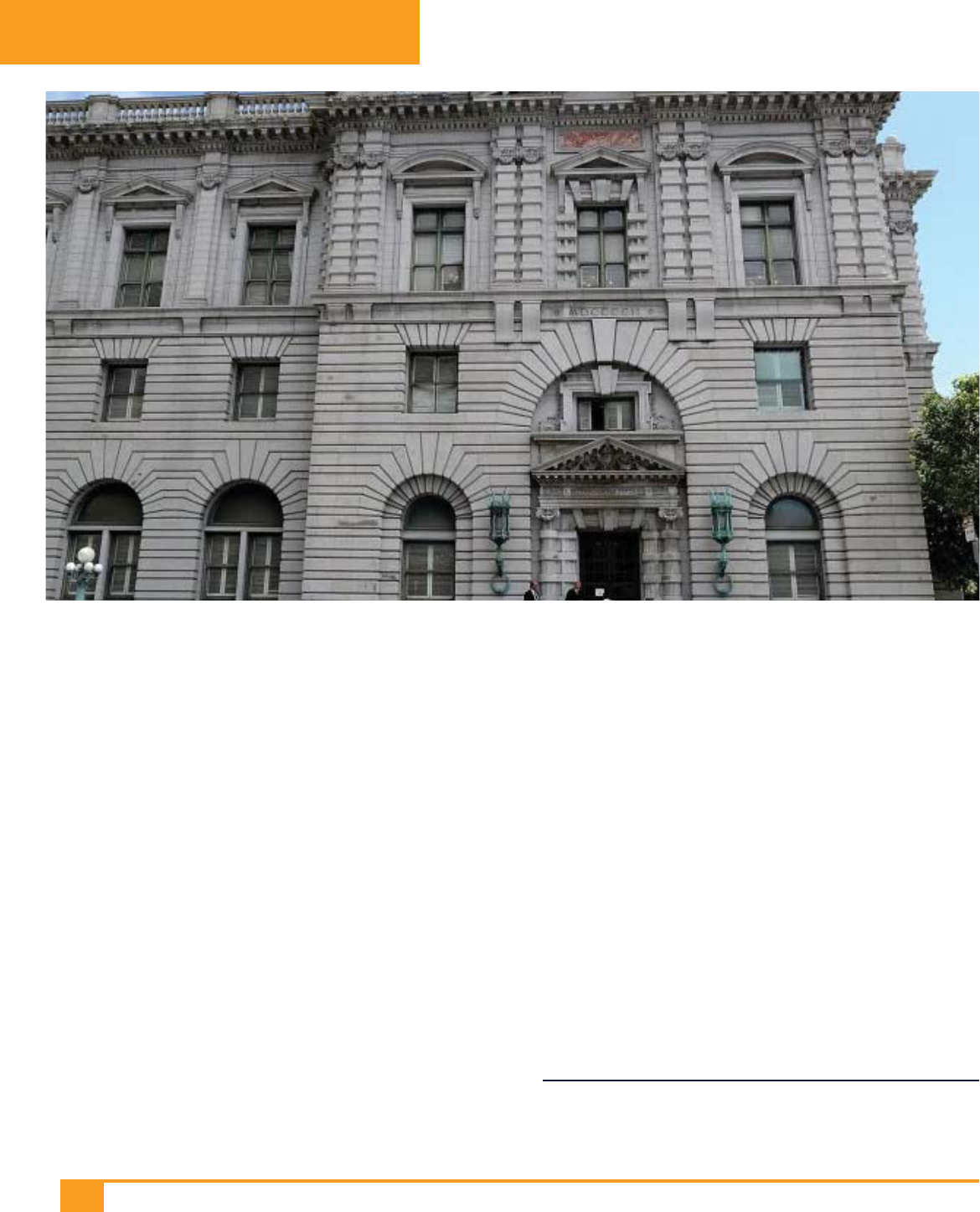

A growing number of courts have found that laws

criminalizing homelessness violate the Constitution

and anti-discrimination laws. In April 2019, the

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit issued an

opinion in Martin v. City of Boise

2

—a case filed by the

Law Center, Idaho Legal Aid, and Latham & Watkins—

affirming that the Eighth Amendment of the U.S.

Constitution prohibits enforcement of laws criminalizing

sleeping, sitting, and lying down outside against people

with no access to indoor shelter. In deciding the merits

of the case, the Court concluded:

“[A]s long as there is no option of sleeping

indoors, the government cannot criminalize

indigent, homeless people for sleeping

outdoors, on public property, on the false

premise they had a choice in the matter.”

3

Criminalization policies and sweeps have also been

condemned by courts as violating Fourth Amendment

property rights, Fourteenth Amendment due process

rights, and First Amendment speech rights. Some state

courts have found that criminalization laws similarly

violate analogous rights under state constitutions.

Criminalization policies and sweeps may also violate

other federal laws, including the Americans with

Disabilities Act.

The criminalization of homelessness is also a matter of

serious concern under international law. Criminalization

of homelessness is discriminatory and constitutes cruel and

inhuman treatment, which violates our obligations under the

Convention Against Torture and the International Covenant

on Civil & Political Rights. Further, the criminalization of

homelessness has a disparate racial impact, in violation of

the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms

of Racial Discrimination.

2 The Ninth Circuit issued its original opinion in Martin v. City of

Boise on September 4, 2018. The City of Boise then filed a petition

for rehearing en banc, which was denied in April 2019.

3 Martin v. City of Boise, 902 F.3d 1031 (9th Cir. September

4, 2019), amended by Martin v. City of Boise, 920 F.3d 584 (9th

Cir. Apr. 1, 2019). The City of Boise has petitioned the U.S. Supreme

Court for certiorari review.

17

The Law Center recognizes that communities struggle

with difficult policy choices over how to reduce

homelessness and often pursue a combination of good

(constructive) and bad (destructive) policies. Rather

than call out individual governments for being the best

or worst, we have identified particularly bad policies

and/or practices of certain governments to include in

our Hall of Shame.

This year, the Law Center has identified seven especially

harmful policies, enacted by: Ocala, Florida;

Sacramento, California; Wilmington, Delaware;

Kansas City, Missouri; Redding, California; the State

of Texas; and the United States federal government.

These policies—ranging from food sharing to

involuntary detention to forced punitive measures—all

encapsulate the misuse of policies that only lead to

cyclical homelessness and poverty.

OCALA, FL: AGGRESSIVE ANTI-

HOMELESSNESS POLICING

In Ocala, Florida, homeless people are strictly policed

in accordance with Ocala’s draconian anti-homeless

ordinances. It is illegal to rest in the open on public

property, which has been heavily enforced by the city.

The city’s “Operation Street Sweeper” and aggressive

policing have even led to a federal lawsuit on behalf

of three unhoused residents. These three plaintiffs have

collectively spent 210 days in jail and been assessed

over $9,000 in fines, fees, and costs due to enforcement

of the trespass and unlawful lodging ordinance alone.

4

4 Complaint, McArdle v. Ocala, Case No. 5:19-cv-461 (M.D.

Fla. 2019).

SACRAMENTO, CA: AGGRESSIVE SWEEPS

AND BANISHMENT OF HOMELESS PEOPLE

The City of Sacramento consistently engages in practices

that seek to isolate and disperse homeless people, even in

the absence of adequate housing alternatives or available

shelters. The City has seized and destroyed encampment

residents’ personal property and caused some of the

residents’ personal injury; it has even fi led its own lawsuit

seeking to declare certain homeless individuals as public

nuisances and to have them banned from public space.

5

5 Sam Stanton et al., Drugs, Thefts, Assaults: Sacramento

Wants to Ban 7 People from Prominent Business Corridor, THE

SACRAMENTO BEE (Aug. 16, 2019, 11:48 AM), https://www.

sacbee.com/news/local/article234082757.html.

HALL OF SHAME

210 days in jail

$9,000+ in fi nes, fees, and costs

For three unhoused residents

under Ocala’s “Trespass and

unlawful lodging” ordinance.

18

KANSAS CITY, MO: FOOD-SHARING

REGULATIONS

Health department officials in Kansas City poured

bleach on chili, soup, and sandwiches being offered to

homeless residents by the organization Free Hot Soup.

Then-mayor Sly James posted on Twitter in support

of the actions conducted by the health department

officials..

6

REDDING, CA: PROPOSED INVOLUNTARY

DETENTION OF HOMELESS PEOPLE

Redding Mayor Julie Winter requested a state of

emergency over homelessness and calling for the

ability to, “hold [homeless] individuals accountable”

by, “[requiring] mental health treatment for the severely

mentally ill, up to and including conservatorship until

such time as the individual has demonstrated the

ability to care for themselves including managing

their finances.”

7

Mayor Winter also wishes to build

a shelter where she can force people experiencing

homelessness to stay for up to 90 days.

“[It] might be a low-security

facility, but it’s not a facility you

could just leave because you

wanted to…You need to get clean,

you need to get sober, you need to

demonstrate self-sufficiency. And

once you do that, you’re free to

go.”

8

6 @MayorSlyJames, TWITTER (Nov. 5, 2018), https://twitter.

com/MayorSlyJames/status/1059549161945743375

7 Letter from Julie Winter, Mayor of City of Redding, to

Honorable Gavin Newsom, Governor of State of California, C

ITY

OF R

EDDING (Nov. 19, 2019), available at https://drive.google.

com/file/d/1lR0NSzB4B-Hr-SZHWuqYg8Vvlnug17ug/view.

8 Emma Ockerman, This California City Wants to Build a

Homeless Shelter That’s Basically a Jail, VICE (Nov. 22, 2019, 4:39

PM), https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/mbmz94/a-california-

mayor-wants-to-build-a-homeless-shelter-thats-basically-a-jail.

WILMINGTON, DE: IMPROPER USE OF NO

CONTACT / STAYAWAY ORDERS

Wilmington has engaged in practices with the intention

of keeping its homeless residents away from certain parts

of town by seeking a “no contact” order with the entire

city as a condition of bail. In Wilmington, the police have

requested that judges issue “no contact” orders prohibiting

direct or indirect contact with the entire City of Wilmington,

the “alleged victim.” Vulnerable residents are thus forced to

choose between agreeing to unreasonable conditions of

release or remaining in jail until their case is resolved.

In November

2018, Health

department

offi cials in

Kansas City, MO,

poured bleach

on food given

to homeless

people.

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT: CREATING AND

WORSENING THE NATION’S HOMELESS CRISIS

Dramatic cuts to federal funding for subsidized housing

led to the modern homeless crisis, and today funding is so

inadequate that only one in four people who are eligible

for housing supports actually receives it. In September 2019,

the Trump Administration’s Council of Economic Advisors

released a white paper claiming that homeless people

remain so because they are “too comfortable” living on the

streets, and calling for policing as a tool, “to help move

people off the street and into shelter or housing…”

10

10 COUNCIL OF ECON. ADVISORS, THE STATE OF HOMELESSNESS

IN AMERICA (2019), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/

uploads/2019/09/The-State-of-Homelessness-in-America.pdf.

19

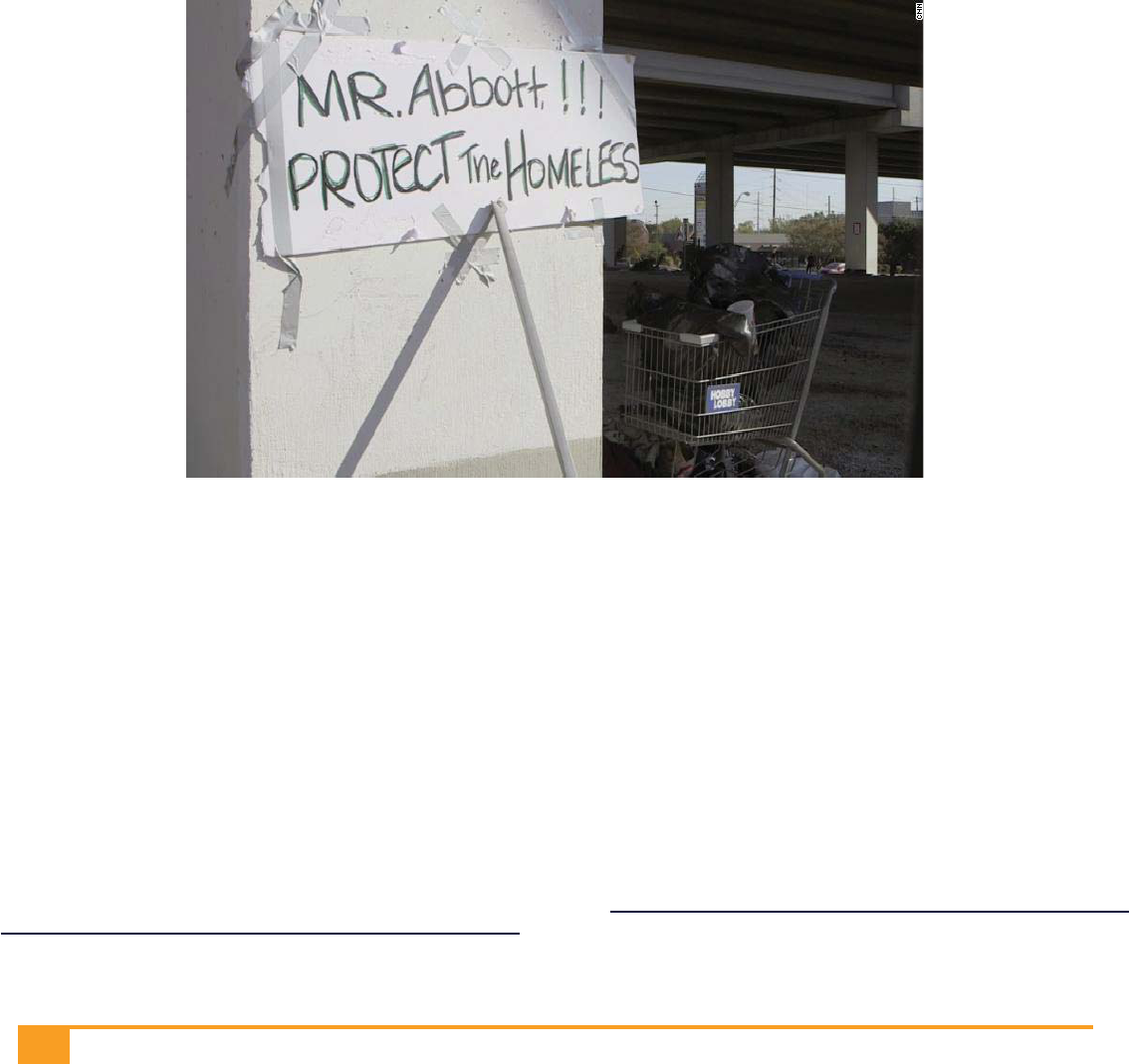

STATE OF TEXAS: FORCING PUNITIVE

APPROACHES TO HOMELESSNESS

Austin amended its camping ordinance in June 2019,

and Texas Governor Greg Abbott rebuked Austin for the

positive law changes and threatened to intervene if the city

did not return to the more draconian version of the ban.

Governor Abbott warned that “all state-imposed solutions”

were on the table, and then ordered Texas Department

of Transportation staff to sweep homeless encampments

from underneath highways in the Austin area.

9

The sweeps

have continued on a weekly basis since the Governor fi rst

ordered them to begin on November 4, 2019.

9 @GregAbbott_TX, TWITTER (July 1, 2019), https://twitter.com/

GregAbbott_TX/status/1145930 019451146245

BEST PRACTICES IN HOUSING, NOT HANDCUFFS

There are

constructive policy

alternatives to

criminalization that

will solve, not punish,

homelessness.

Criminalization is

not an effective

solution for cities

that are concerned

about homelessness.

There are sensible,

cost-effective, and

humane solutions

to homelessness, which a number of communities have

pursued. The Law Center recommends the following policy

and program solutions to homelessness, and highlights

examples where these policies have been implemented,

at least in part. These include long-term solutions that must

be taken to end homelessness, as well immediate and

intermediate term approaches for helping to reduce harm

for the high numbers of people currently living in unsheltered

conditions and encampments:

BEST LONG-TERM SOLUTIONS

HOUSING FIRST AND PERMANENT

SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

Housing is a proven solution to homelessness. Housing

First is premised on the idea that pairing people with

immediate access to their own apartments – without barriers

and without mandated compliance with services - is the best

way to sustainably end their homelessness. One form of

Housing First, Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH), which

combines affordable housing assistance with voluntary

support services demonstrates signifi cant reductions in

criminal justice involvement, with corresponding reduced

costs. In fact, PSH always produces gross savings for

chronically homeless populations.

Four communities have effectively ended chronic

homelessness: In 2017, Bergen County, New Jersey,

became the fi rst, joined since then by Rockford, Illinois,

20

Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and the jurisdictions in the

Southwest Minnesota Continuum of Care.

• 78 communities and three states have effectively

ended veteran homelessness: New Orleans,

Louisiana, was the fi rst city in 2014, Virginia was the

fi rst state in 2015.

• Since 2017, Marin County, California, has reduced

chronic homelessness by an impressive 28% and

overall homelessness by 7% using a system-wide

Housing First approach.

• In Charlotte, North Carolina, permanent supportive

housing reduced arrests of residents by 82%.

• A study of Housing For Health, a division of the Los

Angeles County Department of Health Services

found that the PSH program not only saved over $6.5

million by the second year of its implementation, but it

also reduced emergency room visits by 70% and kept

people off of the streets.

• A 2015 report on permanent supportive housing in

Massachusetts showed that using a Housing First

model saved an average of $9,339 per formerly

homeless person.

• A study of chronically homeless individuals in Seattle,

Washington, found that costs decreased by 60%

per individual after one year in housing—even after

factoring in the cost of housing and supportive services.

82%

70%

60%

Charlotte, NC:

Permanent supportive

housing reduced

arrests of residents.

Seattle, WA: Costs

decreased per

individual after one

year in housing.

S

S

i

n

Los Angeles County,

CA: Permanent

supportive housing

reduced emergency

room visits.

HOUSING FIRST

21

USING VACANT AND SURPLUS PROPERTY

FOR HOUSING AND SERVICES

Governments should use their vacant and surplus

property in their community to provide housing and

needed services to homeless people. All levels of

government own real property that is vacant and/or

surplus to their governmental needs. These unused assets

can be turned to productive use if they are made available

to provide needed housing, shelter, and services to people

experiencing homelessness.

• The federal Title V program, authorized under the

McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, grants

states, local governments, and 501(c)(3) non-profi t

organizations with a right of fi rst refusal to free federal

surplus property for homeless housing and services.

More than two million Americans in 30 states are

served by Title V property conveyances, which have

provided access to approximately 500 buildings

on nearly 900 acres of land in 30 states across the

country.

DEDICATED FUNDING FOR HOUSING AND

S

ERVICES

Local governments are dedicating funding to housing

and services to people without housing. Examples

include:

• In November 2018, San Francisco, California, voters

approved Proposition C, which places an average

0.5% gross receipts tax on companies earning in

excess of $50 million each year to fund homeless

housing and emergency services. The voter measure is

estimated to raise as much as $300 million each year

for housing, mental health, and emergency services

from as many as 400 companies.

• Measure H, a sales tax approved by Los Angeles,

California, voters in 2017, raises sales tax by one-

quarter of a cent, and it is expected to raise about

$355 million annually for ten years to fund homeless

services, including health care and job training.

• The Miami-Dade County, Florida’s Homeless and

Domestic Violence Tax in Miami-Dade County, FL,

imposes a 1% tax on all food and beverage sales by

establishments licensed by the state to serve alcohol on

the premises, excluding hotels and motels. 85% of the

tax receipts go to the Miami-Dade County Homeless

Trust, and it raises some $20 million a year to fund

emergency, supportive, and transitional housing in

Miami-Dade County.

BEST INTERMEDIATE-TERM

PRACTICES

TINY HOME IN-FILL

Tiny homes, while not a total solution to homelessness,

are a rapidly implementable method of providing people

experiencing homelessness with immediate access to

private, indoor space. Accessory dwelling units (“ADUs”),

one type of tiny home, are independent living units sited

on the property of a single-family home. In addition to

providing an affordable housing option, ADUs can also

increase access to high-quality neighborhoods near to

educational and employment opportunities and public

transportation.

• The BLOCK Project in Seattle, Washington, is

a good example of an ADU model that takes

a community-building approach to homeless

housing by placing a pre-fabricated tiny home on

single-family residential lots. The tiny homes are

125 square feet and designed to be self-suffi cient,

including a kitchen, bathroom, sleeping area,

solar-panels, greywater system, and composting

toilet. The BLOCK project relies on volunteer

homeowners, and uses a questionnaire to match

hosts and residents and provides ongoing support

through a social worker. Residents have an

indefi nite rental contract, allowing them to take

as much time as they need to transition to other

housing, or to stay if they need to. Residents pay

30% of their income on rent, divided between

the host family, a maintenance program, and

reinvestment into building new homes.

22

“The BLOCK Project builds communities of com-

passion throughout Seattle, engaging individuals

and their neighborhoods to welcome someone

experiencing homelessness into their lives.”

-The BLOCK Project

23

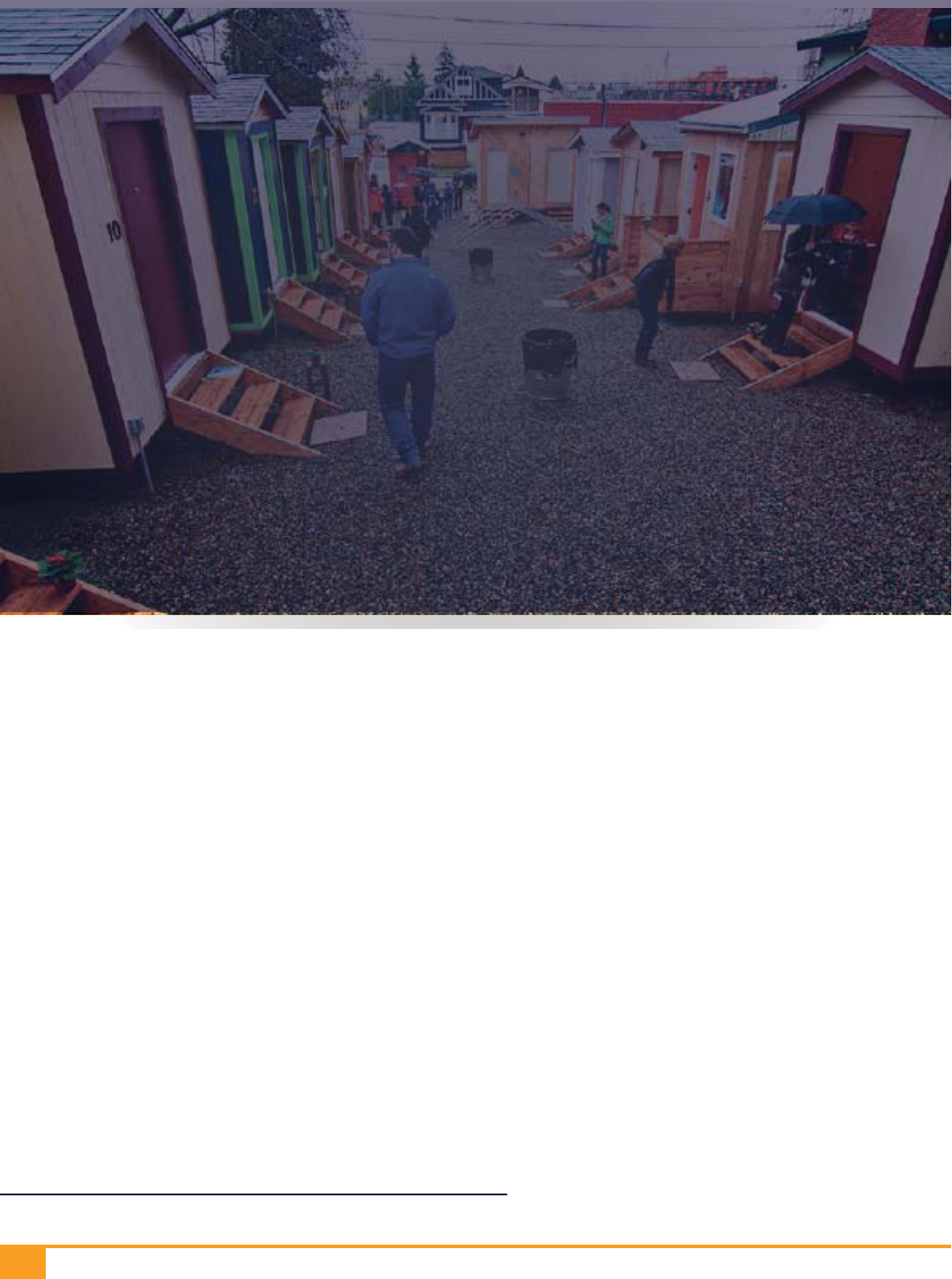

TINY HOME VILLAGES

Tiny home “villages” are another housing model that can

provide at least temporary housing and/or shelter to

people who lack it. These villages offer residents spaces

that are often more comfortable and private than traditional

shelters, can often better accommodate persons with

disabilities who cannot live in congregate shelters, are

more fl exible to construct, signifi cantly less expensive, and

require less land.

• Seattle, Washington, maintains nine villages of tiny

homes as part of a multifaceted partnership with faith-

based organizations, building trade organizations,

and the Low Income Housing Institute. These villages

allow the City of Seattle to house 283 homeless

residents and they boast exit rates to permanent

housing comparable to other shelter programs.

• In October 2019, Denver, Calorado, unanimously

voted to allow 70 square foot tiny home communities

as a matter of right in industrial, commercial, and

mixed-use areas. Church parking lots and residential

areas can also host a village, and permits can be

renewed yearly at the same location for up to four

years, after which they village must move to a new

location.

BEST IMMEDIATE STEPS TO

REDUCE HARM

TEMPORARY SHELTER FACILITIES

Many cities have downtowns with commercial spaces that

are vacant while they await new renters or remodeling.

Private owners can donate these spaces for use as shelter

while they are vacant in order to help alleviate unsheltered

homelessness, and cities can help facilitate the process.

• Portland-Multnomah County, Oregon, is

working with local businesses to facilitate using

temporarily vacant commercial spaces for

immediate sheltering purposes. The city works with

businesses that have vacant space available for

at least a few months to inspect and evaluate the

property and make any modifi cations necessary

to safely house at least 100 people experiencing

homelessness at a time.

TEMPORARY ENCAMPMENTS

Temporary authorized encampments can help people

experiencing homelessness enjoy a secure, private place

to shelter themselves and cities manage their public spaces.

It is critical that temporary encampments should only be

undertaken with an explicit plan for how people living in

the encampment will eventually be placed into permanent

housing.

Encampments are not fully adequate housing, and we

should not accept the existence of permanent encampments

as part of the American cityscape. It is also critical that

the existence of authorized encampments not be used

as an excuse to criminalize those for whom they may not

be appropriate. That said, authorized encampments can

help bring order and services to otherwise unorganized

unsheltered homelessness, benefi ting both its temporary

residents and housed residents in the surrounding community.

A full set of case studies and best practices can be found in

our Tent City USA report.

11

11 NAT’L L. CTR. ON HOMELESSNESS & POVERTY, TENT CITY,

USA: THE GROWTH OF AMERICA’S HOMELESS ENCAMPMENTS

AND HOW COMMUNITIES ARE RESPONDING 8 (2017), http://

nlchp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Tent_City_USA_2017.

24

For cities interested in establishing temporary outdoor

encampments as an interim solution to homelessness,

the Law Center developed a set of guiding principles

for addressing temporary encampments (available at

Appendix B), based on case studies and nationally

recognized best practices. The U.S. Interagency Council

on Homelessness has also released guidance that can help

cities to regulate temporary outdoor encampments as an

interim solution to unsheltered homelessness.

12

• The Mesilla Valley Community of Hope in Las Cruces,

New Mexico, hosts a permanent encampment with

a co-located service center, providing expanded

shelter capacity and a safe space for a self-governing

encampment.

• Washington State permits religious organizations to

temporarily host encampments on their property and

places limits on the number of restrictions municipalities

can impose.

pdf [hereinafter TENT CITY, USA].

12 See Ending Homelessness for People Living in Encampments:

Advancing the Dialogue, UNITED STATES INTERAGENCY

COUNCIL ON HOMELESSNESS, https://www.usich.gov/tools-

for-action/ending-homelessness-for-people-in-encampments/

(Aug. 13, 2015); Caution is Needed When Considering “Sanctioned

Encampments” or “Safe Zones”, UNITED STATES INTERAGENCY

COUNCIL ON HOMELESSNESS, https://www.usich.gov/tools-

for-action/caution-is-needed-when-considering-sanctioned-

encampments-or-safe-zones/ (May 25, 2018).

CLEAR PROCEDURES FOR CLOSING

E

NCAMPMENTS THROUGH HOUSING

Understanding the need for communities to regulate public

spaces, encampments should only be removed through

clear processes, with adequate notice, and a requirement

that the affected persons be provide adequate alternative

housing. Putting into law the commitment to closing

encampments through housing the individuals living there

encourages communities to take an approach that will

permanently end the need for the encampments.

• Settlements in Orange County, California, helped

resolve an 800-person encampment through

rehousing and sheltering rather than arrests. Permanent

features of the settlement limits anti-camping and

loitering enforcement against homeless people until

cities within Orange County establish suffi cient shelter

space to meet their needs. The offered shelter beds

must be available within the same zone of the county

as where the person subject to enforcement lives,

and the offers must be appropriate to the individual’s

medical needs, otherwise the encampment can remain

in place. The settlement also sets forth countywide

standards for shelters, including a grievance process.

Seattle houses

283 homeless

residents through

tiny homes

25

• Charleston, South Carolina, ensured adequate time

for planning, outreach, housing and services to close

a 100-person encampment through housing most of its

residents, without a single arrest.

• Indianapolis, Indiana, adopted an ordinance

requiring residents be provided with adequate

alternative housing before an encampment can be

evicted, and mandates at least 15 days’ notice of

planned evictions to encampment residents and

service providers.

• Charleston, West Virginia, settled litigation by

adopting an ordinance requiring that encampment

evictions cannot proceed unless residents are provided

with adequate alternative housing or shelter, and

providing 14 days’ notice to encampment residents

and service providers of planned evictions, and that

storage facilities will be made available for homeless

individuals.

SAFE PARKING LOTS

Governments should establish safe and accessible

places for people to park vehicles used as shelter. To

accommodate the growing number of people residing

in vehicles, some communities have taken initial steps to

provide safe, legal lots for people living in vehicles to park

them.

• Eugene, Oregon, allows public and private entities to

host up to six vehicles for overnight parking. Each site

must ensure availability of sanitary facilities, garbage

disposal services, and a storage area for campers to

store any personal items so that they are not visible

from any public street.

• In June 2019, Oakland, California, established the

fi rst Safe Lot for RVs in the Bay Area. The new city-

sponsored lot will host as many as 50 RVs for up to

six months, and it provides hookups for electricity and

water. It also has on-site toilets and security.

Encampments should

only be removed

through clear

processes, with

adequate notice

26

PREVENT HOMELESSNESS BEFORE IT

H

APPENS

Cities should prevent homelessness by expanding

protections for low-income renters. While many

communities across the country are working to end

homelessness, infl ows into homelessness exceed the pace

at which homeless people become rehoused. To end our

homelessness crisis, we must prevent housing loss before

it happens. Strong renters’ rights can be immediately

implemented to reduce housing instability, remove barriers

to housing access, and prevent homelessness.

• In many states, renters in privately owned rental

housing may be evicted after their lease has expired,

even if they are responsible tenants. In February 2019,

the Oregon state legislature enacted Senate Bill 608

—the fi rst statewide just cause and rent stabilization law

in the country. The bill limits rent increases to 7% each

year, and it requires landlords to have good cause

for evicting renters. Just cause eviction laws limit the

reasons by which renters may be legally evicted from

their housing, and they are most effective when paired

with rent stabilization policies which limit annual rent

increases to a reasonable amount.

• In late 2017, New York City, New York, became

the fi rst city to guarantee a right to counsel for low-

income tenants in housing court. Reversing a trend in

favor of evictions, with counsel, 84% of tenants remain

in their homes. Moreover, a study done on behalf of

the New York City Bar Association’s Pro Bono and

Legal Services Committee found that providing free

legal counsel to low-income tenants at risk of eviction

would result in a net savings to the city of $320 million

each year.

With state and local budgets stretched to their limit, rational,

cost-effective policies are needed—not ineffective, punitive

measures that waste precious taxpayer dollars. Local and

state governments should redirect resources currently spent

on criminalizing homelessness toward proven solutions to

homelessness.

27

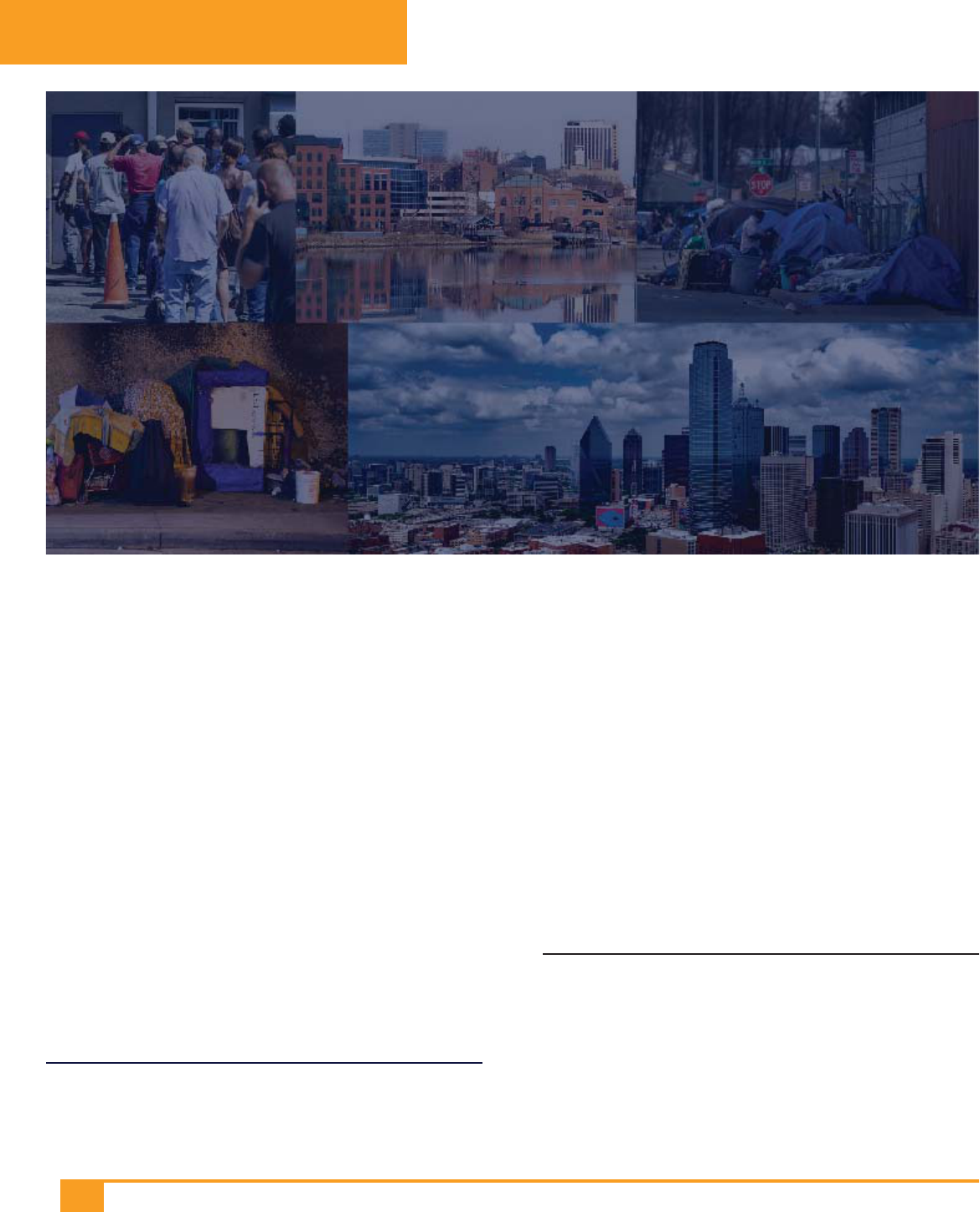

H

omelessness is a national crisis that affects communities in all parts of the country. But we can

solve it. There is ample and growing evidence that housing is the solution to the national crisis

of homelessness. Housing people who lack it saves public money. It improves public health. It

improves public safety. And, it improves the lives—or even saves the lives—of people who would otherwise

struggle for survival in shared public space for lack of any other options.

Even though we know what solves homelessness, and despite the success of at least 78 communities and

three states in effectively ending local veteran homelessness through housing and supportive services, all

levels of government have failed to invest in housing solutions. Instead, a growing number of cities have

taken punitive approaches to homelessness that fail to reduce the number of people living on the streets,

waste limited taxpayer dollars, compromise public health and safety, and cause acute human suffering in

the process. Policies that punish homeless people for living outside—even when they have no other place

to live—refl ect the worst of our prejudices and fears. Moreover, the policies wholly fail to address the

systemic causes of homelessness that have driven the crisis and, if corrected, can solve it.

This report discusses a thirteen-year trend in laws that criminally or civilly punish homelessness, using data

from 187 cities across the country.

13

It also describes common practices aimed at displacing, or even

banishing, homeless people from public space. We discuss why this troubling legal trend harms cities,

exacerbates racial and other social inequities, and wastes money and energy on cruel, often illegal,

policies that are doomed to fail.

13 The 187 cities featured in our research were chosen in 2006 based on their geographic diversity (e.g. they include urban and rural

communities in all regions of the country), and the availability of the cities’ municipal codes online.

INTRODUCTION

HOMELESSNESS IS A LARGE AND GROWING

CRISIS

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD) estimates that roughly 553,000 people experienced

homelessness in 2018,

14

with over one third of those living

in an unsheltered environment.

15

This represents a growth

in overall homelessness, and the third year in a row that

unsheltered homelessness has increased nationwide. Most

of the largest increases in unsheltered homelessness were

reported in Western states. Indeed, between 2015 and

2017, California and Washington together accounted for

over half of all people sleeping unsheltered in the country.

16

Even these stark numbers signifi cantly understate the problem.

Obtaining an accurate count of the number of homeless

people in America has proven to be a nearly impossible

task due to multiple factors—including inconsistent local

implementation of the count methodology and the failure to

count homeless people in places where they may be living.

17

Homeless people who are incarcerated, for example, are

excluded from most offi cial counts of people experiencing

homelessness which can severely compromise count data

in an era of increasing criminalization of homelessness

and mass incarceration. The Continuum of Care (CoC)

for Houston, Texas, performed an “expanded” Point-in-

Time count in 2017 which included homeless individuals in

county jails. Including the incarcerated homeless population

increased the total number of homeless individuals counted

14 U.S. DEP’T OF HOUS. & URBAN DEV., THE 2018 ANNUAL HOMELESS

A

SSESSMENT REPORT (AHAR) TO CONGRESS 4 (2018), https://www.

hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2018-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

[hereinafter AHAR]. The point-in-time (“PIT”) count is conducted for

one night during the last ten days of January each year, with the

goal of estimating the number of people experiencing homelessness

as well as within particular populations. Id. at 6.

15 Id. at 10. HUD defines unsheltered homelessness as “people

whose primary nighttime location is a public or private place

not designated for, or ordinarily used as, a regular sleeping

accommodation for people (for example, the streets, vehicles, or

parks).” Id. at 3.

16 Exploring the Crisis of Unsheltered Homelessness,

N

AT’L ALLIANCE TO END HOMELESSNESS (June 20, 2018), https://

endhomelessness.org/exploring-crisis-unsheltered-homelessness/.

17 See generally NAT’L L. CTR. ON HOMELESSNESS & POVERTY, DON’T

C

OUNT ON IT: HOW THE HUD POINT-IN-TIME COUNT UNDERESTIMATES

T

HE HOMELESSNESS CRISIS IN AMERICA (2017), https://nlchp.org/wp-

content/uploads/2018/10/HUD-PIT-report2017.pdf [hereinafter

DON’T COUNT ON IT].

28

by 57%.

18

These shortcomings warn against relying on HUD

data to present a realistic picture of the homeless crisis, or

even to demonstrate trends.

19

Other data sets present a more accurate view of the size

and nature of the homelessness crisis. According to the

U.S. Department of Education,

20

almost 1.4 million school

children experienced homelessness during the 2016-

2017 school year.

21

Some of these children were among

the estimated 4.4 million poor people in 2017 who were

temporarily sleeping on the fl oors or couches of family or

friends because they could not afford their own housing.

22

A 2001 study using administrative data collected from

homeless service providers estimated that the annual

number of homeless individuals is 2.5 to 10.2 times greater

than can be obtained using a Point in Time count.

23

18 Id. at 12.

19 Id. at 6; see also Kim Hopper et al., Estimating Numbers

of Unsheltered Homeless People Through Plant-Capture and

Postcount Survey Methods, 98 A

M. J. PUB. HEALTH 1438, 1442

(2008), ht tp://ajph.aphapub lications.org/doi/abs/10. 2105/

AJPH.2005.083600; Maria Foscarinis, Homeless Problem Bigger

than Our Leaders Think: Column, USA T

ODAY (Jan. 16, 2014, 7:35

PM), http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2014/01/16/

homeless-problem-obama-america-recession-column/4539917/.

20 The U.S. Department of Education uses a different definition of

homelessness than HUD.

21 National Overview, NAT’L CTR. FOR HOMELESS EDUC., http://

profiles.nche.seiservices.com/ConsolidatedStateProfile.aspx (last

visited Nov. 19, 2019).

22 State of Homelessness, NAT’L ALL. TO END HOMELESSNESS,

https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/

homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-report/ (last visited

Nov. 19, 2019).

23 Stephen Metraux et al., Assessing Homeless Population Size

Through the Use of Emergency and Transitional Shelter Services in

1998: Results from the Analysis of Administrative Data from Nine US

Jurisdictions, 116 PUB. HEALTH REP. 344 (2001).

29

THE GAP BETWEEN INCOMES AND THE

COST OF HOUSING IS A PRIMARY CAUSE OF

HOMELESSNESS

Rising rents,

24

historically low rental vacancy rates,

25

and

the decline of federally subsidized housing

26

have led

to a critical shortage of affordable housing units.

27

This

affordability crisis is further exacerbated as wages remain

relatively stagnant alongside skyrocketing housing costs. In

Santa Clara County, California, for example, household

incomes at 30% of area median income grew by 15%,

while rental prices in the least expensive quartile of units

grew by 36%.

28

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition,

which publishes an annual report on the affordable housing

gap, there are only 35 available, affordable housing

units for every 100 extremely low income (“ELI”) renter

households.

29

This housing gap is even more severe in many

of the nation’s large and growing metropolitan areas. In

Los Angeles, California, for example, there are only 17

affordable and available units for every 100 ELI renter

24 The U.S. average rent is $1,465 as of June 2019, increasing

2.6%since the beginning of the year. At the end of 2018, the

national average rent was $1,419, a 3.1%increase from the year

prior. Drastic rent increases are not confined to major cities such as

New York and San Francisco; small cities experienced the most rent

fluctuation in 2018, with double digit rent increases in Odessa, TX,

Midland, TX, and Reno, NV. Balazs Szekeley, 2018 Year End Rent

Report, RENT CAFE BLOG (Dec. 13, 2018), https://www.rentcafe.

com/blog/rental-market/2018-year-end-rent-report/.

25 Low vacancy rates keep rents high. The national vacancy rate

dropped to 4.4% for both owner-occupied and rental units in 2018,

the lowest point since 1994. J

T. CTR. FOR HOUS. STUDIES OF HARVARD

UNIV., THE STATE OF THE NATION’S HOUSING 1, 27 (2019), https://www.

jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_State_of_

the_Nations_Housing_2019.pdf [hereinafter S

TATE OF THE NATION’S

HOUSING].

26 Since the mid-1980’s, our nation has lost subsidized housing

units at a rate of approximately 10,000 per year. Ed Gramlich,

Public Housing, N

AT’L LOW INCOME HOUS. COAL. (2017), https://nlihc.

org/sites/default/files/AG-2017/2017AG_Ch04-S04_Public-

Housing.pdf. We cannot recover from the homelessness crisis

without significant reinvestment in federally subsidized housing for

low-income people.

27 See e.g., Freddie Mac: Rapidly Growing Metros are Losing

Affordable Housing at Alarming Rates, FREDDIE MAC, https://

freddiemac.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/

freddie-mac-rapidly-growing-metros-are-losing-affordable-

housing (last visited Nov. 27, 2019).

28 BAY AREA ECON. INST., BAY AREA HOMELESSNESS: A REGIONAL VIEW

OF A REGIONAL CRISIS 22 (2019).

29 Households defined as extremely low income (“ELI”)

have incomes at or below the Poverty Guideline or 30% of AMI,

whichever is higher. NAT’L LOW INCOME HOUS. COAL., A SHORTAGE OF

AFFORDABLE HOMES 2 (2018), https://reports.nlihc.org/sites/default/

files/gap/Gap-Report_2018.pdf.

households. In Las Vegas, Nevada, that number drops to

only 10 affordable and available homes.

30

The private market has not been a source for solutions; in

fact, local incentives are further skewing the market. Las

Vegas, which already has a dearth of affordable housing,

is funding development incentives that resulted in 100%

of new apartment developments in 2017 being high-end,

luxury units, rather than affordable housing.

31

This is in

line with national statistics that close to 78% of new units

constructed in 2017 and 87% of new units in 2019

32

were

luxary units.

Paying market rents is a diffi cult-to-impossible task.

33

A full-

time worker earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25

would need to work approximately 103 hours per week

for all 52 weeks of the year—the equivalent of two and

a half full-time jobs—just to afford a one-bedroom home

at the national average fair market rent.

34

There is no state,

metropolitan area, or county where a worker earning

minimum wage can afford market rents by working a

30 Id. at 9. These numbers only count households that are currently

renting and therefore do not account for persons experiencing

homelessness.

31 8 Out of 10 New Apartment Buildings Were High-End in 2017,

Trend Continues in 2018, RENT CAFE BLOG (Sept. 21, 2018), https://

www.rentcafe.com/blog/rental-market/luxury-apartments/8-out-

of-10-new-apartment-buildings-were-high-end-in-2017-trend-

carries-on-into-2018/.

32 Id.

33 As rents have risen, wages of low-income American workers

have declined. From 1979 to 2013, while the hourly wages of

high-wage workers rose 40.6% and those of middle-wage workers

grew 6.1%, the wages of low-wage workers fell 5.3%, according

to the Economic Policy Institute. E

LISE GOULD, ECON. POLICY INST.,

WHY AMERICA’S WORKERS NEED FASTER WAGE GROWTH—AND WHAT WE

C

AN DO ABOUT IT 4 (2014), https://www.epi.org/files/2014/why-

americas-workers-need-faster-wage-growth-final.pdf.

34 N

AT’L LOW INCOME HOUS. COAL., OUT OF REACH 1 (2019),

https://reports.nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/OOR_2019.pdf

[hereinafter OUT OF REACH].

30

standard 40-hour per week job.

35

People who are on fi xed

incomes, such as retired seniors and people with disabilities,

are also priced out of the market.

Millions of renters pay more than they can afford

to keep a roof over their heads, and are at risk of

homelessness.

36

According to a June 2019 report by the

Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University,

nearly half of the entire U.S. renter population is “cost

burdened”, meaning that they pay more than 30% of

their incomes toward housing costs.

37

While housing

cost burdens affect renters of multiple income levels,

our nation’s poorest renters feel housing cost burdens

most acutely. Indeed, renters are considered severely

cost-burdened when they spend more than 50% of their

incomes on housing.

38

Today, 71% of ELI households

are severely cost burdened.

39

Housing cost-burdened renters are left with little

income for other necessities like food, medicine,

child care, and transportation. They have no financial

35 Id. at 2. This statistic is for 2-bedroom units at fair market rent.

36 The majority of renter households are low-income, with

53%of all renter households earning less than $35,000 annually,

and 60% of those earning less than $15,000 each year. JT. CTR. FOR

HOUS. STUDIES OF HARVARD UNIV., AMERICA’S RENTAL HOUSING 1 (2017),

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/harvard_jchs_

americas_rental_housing_2017_0.pdf.

37 STATE OF THE NATION’S HOUSING, supra note 26, at 4.

38 The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes, NAT’L LOW

INCOME HOUSING COALITION, https://reports.nlihc.org/gap/about

(last visited Nov. 19, 2019).

39 Id.

cushion against emergencies or sudden interruptions in

income from job loss, divorce, or other destabilizing

life events. Meanwhile, federal housing subsidies have

shrunk dramatically in recent decades, and only 24%

of people eligible for housing assistance receive it.

40

In this environment, low-income renters face a constant

risk of housing loss and homelessness.

People of color are especially harmed by the affordable

housing gap. Approximately half of all renters in this

country are people of color. According to the 2019

Harvard Report, the cost-burdened share is highest

among Black renters at 54.9%, followed closely by

Hispanics at 53.5%.

41

The rates for Asians and other

minorities are lower at 45.7%, but still above the white

share of 42.6%. Among homeowners, 30.2% of Blacks,

29.6% of Hispanics, and 27.3% of Asian/others were

cost burdened in 2017, compared with 20.4% of White

homeowners.

42

A growing body of research demonstrates the causal link

between unaffordable rental housing and homelessness.

A recent study from UCLA found that housing costs are a

signifi cant factor in California’s homeless crisis.

43

The study

compared homeless rates and housing costs in all 50 states

and Washington, DC, and found that, in general, states

with higher housing costs have higher homeless rates. The

study also found that states with higher incomes and more

housing supply had lower rates of homelessness.

A similar study, Dynamics of Homelessness in Urban

America, examined the relationship between housing

costs and homelessness in the 25 largest U.S. metropolitan

areas, drawing on data from the U.S. Census Bureau,

HUD, and the housing website Zillow.

44

The study found

a strong correlation between homelessness and rental

costs. The study also predicted marked increases in

homelessness with rising rental costs. For example, the study

predicted over 6,000 more people would experience

homelessness in New York City if rents increased by 10%;

in Los Angeles, the increase would be over 4,000 more

40 Erika C. Poethig, One in Four: America’s Housing Assistance

Lottery, URB. INST. (May 28, 2014), https://www.urban.org/urban-

wire/one-four-americas-housing-assistance-lottery.

41 STATE OF THE NATION’S HOUSING, supra note 26, at 32.

42 Id.

43 Andrew Khouri, High Cost of Housing Drives Up Homeless

Rates, UCLA Study Indicates, L.A. TIMES (June 13, 2018, 5:00 AM),

https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-ucla-anderson-forecast-

20180613-story.html.

44 CHRIS GLYNN & EMILY B. FOX, DYNAMICS OF HOMELESSNESS IN

URBAN AMERICA 1 (July 28, 2017).

people.

45

Unaffordable rents result in evictions for non-

payment of rent, which is a direct cause of homelessness.